Above: Buddie, shown standing beside the automobile with the hat and cigar, chats with Louis Chevrolet at the 1909 Atlanta Speedway Races

Asa Candler, Jr'.’s greatest passion in a life filled with passions was automobiles. It was his number one fixation for more than a decade, and he threw his energy, his money, and his professional reputation behind promoting driving as a popular sport.

It’s likely that he encountered his first automobile in Los Angeles in 1899. Prior to that he lived in Oxford, a remote Georgia village that maintained mule cars well into the electric streetcar era. Not a bustling metropolis of wealth and innovation. It’s possible that he could have seen one in Atlanta before moving to L.A., but the window between graduation and moving west was very brief.

According to the Los Angeles Almanac website, the first car that appeared in the Los Angeles area showed up in in 1897, and by 1904 there were as many as 1600 automobiles on the roads. Buddie worked on San Pedro Ave. near Fourth, and lived at the Hotel Johnson near the intersection of Fourth and Main. That was smack in the middle of the thriving financial district. He lived adjacent to the Westminster Hotel and the Van Nuys Hotel, both luxury properties with impressive amenities like private bathrooms and telephones in every room. He was in the right place at the right time to encounter an early automobile up close.

Family lore suggests that he acquired his first car in Hartwell. In a story relayed by one of his descendants in Elizabeth Candler Graham’s “The Real Ones,” he reminisced about wowing the Hartwell locals by puttering around the tiny town in his steamer car. Corroborating his memory, family lore and preserved documents show that Buddie traveled back and forth between Hartwell and Atlanta to purchase automobile parts. In fact, the frequent travel may have contributed to his distraction from his focus at the mill.

in 1902 his big brother Howard was stationed in New York City, and he convinced their father to let him buy a Locomobile for Coca Cola client calls. Asa, Sr., wasn’t convinced of its necessity and didn’t like the expenditure, but Howard talked him into it. A little brotherly competition could have played a role in Howard’s request. In his 1950 semi-biography, semi-memoir, “Asa Griggs Candler,” Howard reminisced about his father’s love of automobiles that developed over time, but certainly didn’t exist yet in 1902. Based on the pattern of documentation and media, I believe it was Buddie who brought the love of automobiles into the family, and their father, always swayed by Buddie’s charming enthusiasm, was eventually swept up in auto fever.

In 1906 Buddie relocated to Atlanta and began making money in earnest, which he poured into his favorite hobby. In July of 1907 he was listed as the driver of his own car in a city-wide event that gave over 350 orphans a day of fun and pleasure. 104 automobiles, piloted by wealthy local men, lined up to give these children what was likely their first ride in a motorized vehicle.

“104 MACHINES PARADE TODAY

Orphans Will Make Tour of City in Autos. More than 300 Children Will Be Given Day of Pleasure by Owners of Cars, the Parade to Start at 2:30 O’Clock. Will Be Amused at Ponce de Leon.

There will be one hundred and four cars in line this afternoon at 2:30 o’clock when the orphan children’s great automobile parade starts from Trinity Methodist church, at the corner of Whitehall street and Trinity avenue.

With the 356 orphans there will be four teachers from each institution, making 376 in all. The owners of these 104 machines will drive their own cars in the parade.

Each child will be provided with a tin horn and all along the line of march they will make the welkin ring. Ed Inman’s big car will lead the possession and Chief Cumming, of the fire department, will furnish a bugler to go with this car. W. O. Jones will be marshal of the day and will direct the formation of the line on Trinity avenue.

Manager Hugh L. Cordoza. of the Ponce de Leon park, has tendered free access to all the amusement features of the park, ard this is quite a concession when the money cost of taking these 376 people through each amusement place at the park is considered.

There will also be a bountiful supply of ice cream and candies, Wiley contributing the former and the Frank E. Block Company and Harry L. Schlesinger the latter. Gershon Brothers donated 500 wooden saucers and Dr. M. Turner as many spoons.

The parade will be over a mile long, as the 104 cars will be strung out 50 feet apart, and this would stretch out over 5,000 feet, not counting the length of the cars.

When the children are put down at the park the automobiles will disperse their several ways and the children will revel in the delights at Ponce de Leon till 6 o’clock, when five electric cars will be in waiting to take the little fellows back home, there being one car for each home, these cars being tendered free by the Georgia Railway and Electric Company.”

Around this time the annual Vanderbilt Cup races were taking off as an internationally known event. Another event in upstate New York called the Briarcliff Trophy Stock Car Race drew massive crowds in 1908. Family documentation indicates that Buddie was traveling to New York and back for business as the Vanderbilt Cup and Briarcliff Trophy races were peaking in popularity. Due to the timing of these events and Buddie’s skyrocketing obsession with auto racing, one could conjecture that Buddie may have attended one or more of these events in the early 1900s.

In August of 1908 Buddie and Walter headed out on a road-trip to South Carolina, having upgraded to internal combustion engine vehicles which could go much further on a tank of fuel than a steamer could go on a tank of water. At this time Buddie reportedly owned a Peerless, an immensely expensive car for the time period. He had connections to Anderson, SC, possibly through in-laws, so this road trip from Atlanta through Hartwell to Anderson, SC, was likely a visit with family. This may also have been the genesis of his interest in trail-blazing pathfinder road tours.

Quick aside about road tours. When automobiles were new, roads that were smooth enough for auto traffic could be hard to find. Pitted, rutted dirt roads were fine for wagons and carriages, which traveled at slow speeds relative to what an automobile could do. Early cars were never slow by design. Even the earliest steamers could travel a mile a minute, but rough roads restricted most drivers to lower gears. Cities, which often laid down gravel or macadamized their busiest streets, were no help due to traffic congestion of pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages and streetcars. Atlanta’s downtown was paved with Belgian blocks of Stone Mountain and Arabia Mountain granite, which didn’t make for the smoothest ride. Cruising simply wasn’t what it is today.

it was the road tour phenomenon that gave us the open road concept and gave birth to the vast network of smooth streets and highways that we drive on today. In 1907 William K. Vanderbilt broke ground on the first commuter road in America, the Long Island Motor Parkway, so he could drive his beloved collection of cars in conditions more pleasurable than back country roads. But Willie K. was part of a family that could afford to lay down roads wherever they pleased. Your average (but still wealthy) driver had to be more creative.

Driving clubs sprung up and, often in partnership with local newspapers, started sponsoring what were known as “pathfinder tours.” The idea was that drivers would compete to find the fastest, smoothest route between two points and map the pathway with timing records. Winning routes were then published for other motorists to enjoy. These tours defined routes that became major roadways that still exist today.

Buddie participated in a number of pathfinder road tours around Georgia. In November of 1908 he joined the Atlanta Automobile Club and became deeply involved in the organization as a member of the so-called executive committee under club president Ed Inman.

In May of 1909 he set out on a pathfinder road tour sponsored by the Atlanta Constitution to find a drivable route between Atlanta and Macon. Asa, Sr., came along for the ride. As the President of the Chamber of Commerce, Asa, Sr., declared that finding a good road between the two cities made good business sense. Asa, Jr.,’s, route took them south from downtown Atlanta to Hapeville, GA, via a small road called Stuart Ave. That summer he would break ground on an automobile racetrack in Hapeville and fund improvements to Stuart Ave., now Metropolitan Blvd., to bring traffic directly to the track from the city. More about the Atlanta Speedway will appear in a future site update.

As part of his effort to get the speedway built in the summer of 1909, Asa, Jr., convinced his father to bankroll a takeover of the Atlanta Automobile Club, renamed the Atlanta Automobile Association, and install Buddie as its president. This move ousted founder Ed Inman, who went on to start a competing club called the Fulton County Automobile Club. Buddie eventually belonged to both clubs, but tension existed between the two and he clearly favored his own AAA.

Buddie took over the AAA in May, solicited construction bids in June, and put thousands of prison laborers to work in July, with the goal of being finished by October.

It wasn’t finished in October. But it was finished enough for a press tour and a fundraiser. He threw a party with 500 of Atlanta’s most influential people in attendance, a barbecue catered by his friend Lee Barnes and served al fresco, and afterward he invited the guests to stroll around the incomplete track so they could admire its ingenuity. To close the event he and Asa, Sr., petitioned the crowd to pledge money to resurface Stewart Avenue, the road that led straight from downtown Atlanta to Hapeville, so race attendees could travel to the event in comfort.

In November of 1909 the Speedway opened to massive crowds during what was dubbed Automobile Week. A huge auto show and events were held all over the city in celebration of motoring. An event sponsored by the New York Herald and the Atlanta Journal called the Good Roads Tour sent 61 drivers down the eastern seaboard from New York City to Atlanta, with the convoy arriving in time for the participants to take a lap around the new track. Even baseball great Ty Cobb participated and made the difficult trek behind the wheel of his own car.

The following summer Buddie bought a 1910 4-cylinder, 45 HP model H Lozier in a style known known as the Briarcliff. The Daily Times Enterprise of Thomasville, GA, reported the purchase by noting that Asa Candler, Jr., owned a whole “herd” of automobiles, and bought a new car as often as an average man bought suits. The New York Times auto gossip column reported on the expensive purchase, calling it a compliment to Lozier. The story was also picked up by the San Francisco Call and the San Francisco Chronicle. Buddie was becoming a minor celebrity due to his driving prowess.

1910 Lozier Briarcliff H - Note: Not Buddie at the wheel

1910 Lozier Briarcliff - Note: Not Buddie at the wheel

In June of 1910 Buddie embarked on the Atlanta to New York Good Roads Tour. It’s notable that at $5000, his Lozier was one of the most expensive cars in the race. Most competitors’ cars cost $1-2k. Only one other car, a Thomas Flyer valued at $6k, was more expensive than Buddie’s. His Briarcliff was registered as car #30 with passengers brother-in-law Henry Heinz, merchant John S. Cleghorn, music house VP Ben Lee Crew, and F. H. McGill listed as driver. Frank Hardaman ‘Mack” McGill, Jr., was Buddie’s personal driver for several years. In most events where Buddie is credited, Frank McGill did much of the driving. His dependency on pros for wins repeated during his airplane years. Mack worked for Buddie as a registered chauffeur until 1914, at which point he relocated to Miami and opened a motorcycle shop.

Buddie took his Lozier over unpaved roads from Atlanta to New York and arrived as one of only three cars with a perfect score. This meant his timing and speed were consistent and he suffered no mechanical breakdowns. Lozier and the Diamond tire company were excited about the opportunity to advertise the success of their products and ran national advertising campaigns that cited Asa Candler, Jr.’s perfect run.

Fame went to Buddie’s head immediately and he made efforts to keep himself in the headlines as much as possible. He entered his Briarcliff in the 1910 Atlanta Speedway fall races, started rumors and drummed up gossip to raise interest in the track, and published fanciful stories that are in no way believable but were intended to bolster his image as the greatest driver that ever lived.

To drum up press for the November 1910 races he announced that he would embark on a “round the state” pathfinder tour of Georgia in his famed Briarcliff. He claimed his Lozier had never seen a tune-up in its life and would return in equally top condition. He ended his tour with a tan and a bevy of entertaining stories to tell, which he did at length.

In August of 1910 he sued a child for damages when he caught him striking a match on the side of his car. He claimed it was a nuisance to himself and other automobile owners and even took time out of his busy life to show up in court to testify against a child. The young boy was fined, his older brother paid it on his behalf, and the police promised to do a better job watching out for this apparent crime wave. Since, I suppose, there were no more important matters of justice to attend to.

In September of 1910 an article ran in the Wilmington Morning Star (see Gallery) discussing the important qualities of good race car drivers. The upshot was this: Recklessness, thoughtlessness, and “beefiness.” It compared the body size, and in some cases forearm size, of several famous drivers. It then included an anecdote about Buddie and his driver, Mack McGill.

“There was an example this summer on the Atlanta Speedway. In the early practice for a local meet F. H. McGill and Asa Candler, Jr., did all the timing up for Mr. Candler’s giant Fiat 60 [ed note: Fiat 90]. This is a car which is particularly vicious at steering. It yanks and bucks and raises sand, especially on the turns. In every practice spin Mr. Candler could get two or three seconds better time for a round than his driver. Both men are equally fearless and equally skillful. The secret lay in weight and proportionally more strength.

’Beef’ is what is needed. Men pick their race drivers today as they picked football material in the old days.”

In October of 1910 an interesting snippet was printed in the Atlanta Georgian (see Gallery) about a man named Charles Frank, owner of the New Orleans baseball team, gave a glimpse into Buddie’s reputed recklessness and fearlessness behind the wheel. The article claimed that Buddie offered Mr. Frank an opportunity to take a spin around the track in his Pope-Toledo. This car was a seven-passenger touring model, not a racer, but likely a large-engined beast capable of high speeds. Although likely meant with some humor, Mr. Frank’s comment following the lap suggests that he did not feel safe and secure in Buddie’s hands.

“I’d rather go with the wildest one of all then go back in the Pope with Asa Candler, for he is worse than any of ‘em.”

During the November 1910 Atlanta Speedway races a photographer captured four photographs of Buddie’s son, John. In two he posed as a driver in the pilot seat of his father’s Lozier Briarcliff. In January of 1911 Buddie fabricated stories about John as a master driver and sent them around for pickup in newspapers across the country.

John Candler behind the wheel of his father’s Lozier Briarcliff, Atlanta Speedway November Race, 1910

John Candler behind the wheel of his father’s Lozier Briarcliff, Atlanta Speedway November Race, 1910

John Candler drinking a coca cola,, Atlanta Speedway November Race, 1910

John Candler with his father, Left, shown with a cigar in his mouth, Atlanta Speedway November Race, 1910

“AUTOMOBILE NEWS AND GOSSIP

Undoubtedly the youngest racing driver in the world is the four-year-old son of Asa G. Candler, jr., owner of the Atlanta Speedway and himself an amateur driver of ability.

This Lilliputian Knight of the Wheel not only drives his father’s 46-horsepower Briarclif model on the Atlanta Speedway, but is a racing driver of no mean ability. He drove this big powerful Lozier car for one hour, making forty-two miles in that time and carried in the tonneau two newspaper reporters and the senior Candler.

Such a performance would be almost unbelievable were it not for the fact that it is vouched by Howard Sphn, representative of Automobile and Motor Age, Percy Whiting, sporting editor of the Atlanta Constitution, and J. M. Nye, assistant secretary of the speedway in Atlanta, who were all present when this diminutive driver made this really wonderful performance.

Asa Candler, jr., who sat in the mechanic’s seat on one side of the little chap when he was making the run, stated that he would have made a greater mileage in the hour’s time had he not been several times cautioned to slow down. At one time, when taking the lower turn of the track at a 50-mile clip. the car swerved slightly. Master Candler was not in the least affected. Looking up out of the corner of his eve at his father, he merely remarked, “she skidded a little that time, dad.””

The same story ran verbatim in The San Francisco Chronicle, with an added embellishment at the end.

“FOUR-YEAR-OLD PILOT OF A RACING LOZIER

Child Driver Makes Forty-Two Miles in the Course of One Hour.

...Not long ago he was told by his father in a joking way to go out to the garage and get the Lozier and take the family out for a ride. The young man disappeared and when search was made for him half an hour later he was discovered out in the garage making a desperate effort to start the motor. ‘What’s the matter, dad?’ was his comment, as his father appeared. ‘I would have had her around in a few minutes more if you had not come out.’”

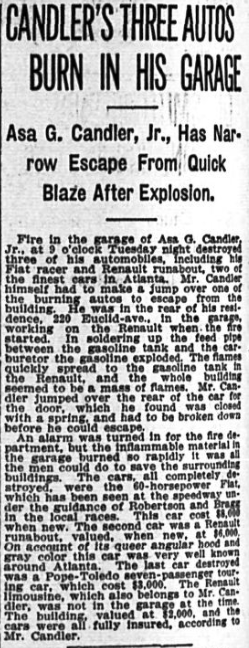

By 1911 the track had proven itself to be too much of a drain on Asa, Sr.’s, finances, so he foreclosed on the mortgage. Then Buddie’s garage where he housed his valuable collection of automobiles caught fire and destroyed his cars in February of 1911. The Briarcliff was not accounted for in this story as one of the damaged vehicles, but there are no indications that he sold it prior to that incident. Since this was less than a month since his story about John driving his Lozier it seems likely he still owned it and it survived the fire. Read more about the garage fire in a future site update.

After the garage fire Buddie’s public interest in cars faded quickly. On October 1, 1911, the Los Angeles Times reported that Asa, Jr., had withdrawn from the Glidden cross-country pathfinding tour, citing severe illness. After this time automobiles faded from his public-facing persona and he moved on to new interests. But he still occasionally appeared in print associated with cars in one way or another.

On July 18, 1911, his baby brother William found himself in hot water when he struck a man on Peachtree Street with a car owned by Asa Candler, Jr. On March 25, 1917, Buddie published a story about a Locomobile that won a hill climb on Ponce de Leon Ave. well past the time when hill climbs were popular and Locomobiles were hot. Given the positioning of the story, he may have earned a little money acting as a 1900s print media influencer.

On April 14, 1917 the last of Buddie’s driving records fell, as an amateur Atlanta driver named Homer C. George beat the standing Atlanta-Knoxville run by four hours. Buddie had set the original record on July 14, 1914.

On November 10, 1934 Buddie’s daughter Helen, Jr., struck a 5-year-old boy with her car, sticking her father with an expensive lawsuit. On August 23, 1935, Buddie was in an accident on the way home from a trip to Florida with his wife and two nephews. While Florence and the two boys were injured, Buddie was not. He claimed the steering suffered a malfunction and the car spun out of control.

The 1920s census shows that he employed a chauffeur named Eli Johnson, and in the book “The Real Ones,” the author claims he later employed a chauffeur named Lige Brown and a backup driver named Samuel “Slim” Green. Aside from pleasure driving, Buddie simply didn’t drive himself around anymore after he relocated out to his Briarcliff property in Druid Hills.

The Lozier Briarcliff was never mentioned again after the cockamamie story about John driving it around the track. The Briarcliff identity shifted from his car to his home and property. Two of the vehicles that brought him fame, a Pope-Toledo and a Fiat-90, died in two separate fires. The other one, his Lozier Briarcliff, simply vanished from the record. For now, the end of the Briarcliff’s story is unknown. It appears to have survived the garage fire, and its contribution to his B-list fame likely influenced his decision to take its name for his new property. But his beloved car and his love of automobiles faded from his life, not with a bang but with a whimper.

Automobiles Gallery

First Cocq Cola automobile, New Y0rk, 1902

1908 Peerless Automobile Ad. Asa Candler, Jr., is confirmed to have owned a Peerless in 1908.

August 8, 1908, The Atlanta Georgian

The Atlanta Constitution, July 20, 1907

November 6, 1908, The Atlanta Georgian

May 25, 1909, The Atlanta Constitution

June 16, 1910, The New York sun

June 17, 1910, The New York times

June 19, 1910, The Atlanta Constitution

June 26, 1910, The Minneapolis Star tRibune

August 27, 1910, The Atlanta Georgian

September 28, 1910, The Wilmington Morning Star

October 26, 1910, The Atlanta Constitution

Washington Herald, January 15, 1911

The San Francisco Chronicle, January 22, 1911

February 8, 1911, The Atlanta Georgian

Note: The 60HP Fiat is misprinted. The car that was lost was the 90HP Fiat driven by George Robertson in the 1909 races.

February 8, 1911, The Tennessean

July 18, 1911, The Atlanta Georgian

March 25, 1917, the Atlanta Constitution

8, 23, 1935, The Atlanta Constitution