Above: Postcard showing the layout of the 2-mile track and the Atlanta city skyline.

First, an oversimplified history of auto racing.

Just before the turn of the 20th century, automobiles roared into existence and captured the imaginations of gear-heads around the globe. But because these early machines were hand-made, bespoke feats of engineering, which made them unaffordable for the average person, their very nature made them impractical playthings of the wealthy. When you hear apocryphal stories about people shouting, “get a horse!” at early drivers, just remember that Henry Ford’s consumer-friendly Model T didn’t come along until 1908. Before that, your average Joe wasn’t in the market for an automobile.

In the earliest days, pitting cars against each other in competition was a pretty obvious and exciting use for the technology. How else could manufacturers and wealthy gadabouts prove their superiority over each other? Besides, by all accounts it was a heck of a lot of fun. Auto racing gained popularity in Europe first, typically over bumpy rural roads on cross-country courses. In 1895 the first true automobile race ran from Paris to Bordeaux, France. That same year, the United States held its first automobile race in Chicago, but the European racing community coordinated better and pulled together many competitions before the U.S. became a real contender.

In 1904, William K. Vanderbilt decided the United States was well overdue for a trophy run of its own. He established the Vanderbilt Cup on Long Island, NY, which was open to international competitors. American auto manufacturers jumped at the chance to demonstrate their viability against their European counterparts. But try as they might, they couldn’t grab a win. In fact, they wouldn’t grab a win until 1908, when George Robertson took the cup in a Locomobile known as Old 16.

Want to hear her start up? Give a listen at 0:30:

The Vanderbilt Cup was a massive sports event, pulling record attendance numbers and inspiring wealthy men across the country to travel to New York just to watch. Prior to Old 16’s race, in February of 1908, a round-the-world race from New York to Paris captured imaginations and made headlines. Only three of the six participants made the full run, and an American, a Thomas Flyer, came in first on July 30th. So when George Robertson’s Locomobile clinched the Vanderbilt Cup in the autumn of 1908, proving America’s mechanical might, the victory became a watershed moment for auto racing.

Due to the hazards of driving on country roads, which resulted in both driver and spectator deaths, the idea of specially dedicated racetracks gained popularity. Controlled conditions, spectator barriers, and consolidated action certainly sounded more appealing than sitting idle on the side of a road, waiting for competitors to roar into view and disappear in a cloud of dust. While many regions kicked off race track projects, the most notable one for the purpose of this story was Indianapolis, Indiana. Immediately following Old 16’s win, planning began for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, better known today as the home of the Indy 500 and the United States Grand Prix. Construction broke ground in March of 1909 and the 2-mile course opened in June with a balloon race with over 40,000 attendees.

What does this have to do with Asa Candler, Jr.?

Travel timing gleaned from personal correspondences suggests a strong likelihood that Buddie Candler attended the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup. He was already infatuated with automobiles, having purchased his first car during his time in Hartwell, GA, and having participated in automobile-themed events in Atlanta. He had gotten his big brother Howard interested in automobiles, who in turn convinced their father, Asa, Sr., to buy a Locomobile for the NYC Coca Cola office in 1902. By his own admission in a letter to Howard, Asa, Sr., believed cars to be a passing fancy, nothing worth investing in. But a few years later Buddie moved home, got Asa, Sr., swept up in his enthusiasm, and they both became vocal supporters of local automobile events. So when racing fever swept the nation, both Asas were game.

Here’s how the timeline plays out:

In 1907, Buddie moves back to Atlanta and settles into the city’s business community. In June of that year he participates in the city’s largest automobile event to date, which features 104 machines in a parade supporting local orphanages.

In July of 1908, he attends a political event thrown by a nominee for the Governor’s office, where he rides in the car of honor with the candidate and another man named Edward Durant.

Also in July of 1908, an American-made Thomas Flyer driven by George Schuster takes first place in the 1908 New York to Paris Race.

In October of 1908, George Robertson takes the Vanderbilt Cup for the U.S., marking the nation’s first Vandy win.

In November of 1908,, just thirteen days after Old 16’s win, Edward Inman establishes the Atlanta Automobile Club, with Buddie as one of the club’s officers. The stated goal of the club is to promote automobile events in the city and build a fancy clubhouse. They later change their name to the Fulton County Automobile Club to avoid sharing initials with the Atlanta Athletic Club.

In March of 1909, Indianapolis announces that they will build the world’s greatest automobile racing track, and that Indianapolis will be the undisputed center of the automobile industry. They break ground on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

That same spring Buddie and Ed Durant stir up rumors in the Atlanta business community when they start spending lots of time in Hapeville, GA, just south of downtown Atlanta. Leveraging assets available to him as manager of his father’s Candler Investment, Co., Buddie buys up parcels of farmland from Hapeville residents. He and Durant respond evasively when asked publicly about their intentions., even claiming when pressed that they’re planning to establish a very large cemetery (foreshadowing Westview?). Behind the scenes, however, they take a proposal to Asa, Sr., who agrees to partially fund construction of their secret project.

In April of 1909, Asa Candler, Sr., rallies the business community around the idea of hosting a week-long automobile industry national event in November.

On May 23, 1909, Buddie and Durant announce their plans: they will build a $225k (well over $6mm today) world-class racing track that will establish Atlanta as a dominant force in automobile greatness.

Atlanta was now in a race with Indianapolis. Other regional tracks had already been built in the South, such as the one in Savannah. In fact, Birmingham, Alabama, started hosting auto racing events as early as 1906. But in 1909, Indianapolis was the project to beat. Throughout Buddie’s life he demonstrated a tendency to rise to the challenge when another metropolitan area claimed greatness. He couldn’t abide by another city suggesting it was better than Atlanta. He looked at Savannah and Birmingham and said, “Why not Atlanta?” But he looked at Indianapolis and said, “Oh, no you don’t!”

The day after their announcement, Buddie and Durant participated in a Pathfinder tour sponsored by the Atlanta Constitution. The purpose of the tour was to find and map the best, smoothest, fastest roads for automobiles between Atlanta and Macon. Buddie convinced Asa, Sr., to come along for the ride, and they started their route with purpose down Stewart Avenue (now Metropolitan Parkway), which was a long stretch of road that ran directly between downtown and Hapeville. Evidence suggests that they used the Constitution’s pathfinder tour to finalize their plans for the track, which included identifying exactly how race attendees would get from the more populated city center to the outskirts where the track would stand.

May 25, 1909, The Atlanta Constitution

In June the two Asas and Ed Durant accepted bids from construction companies who were willing to work within their budget against an aggressive timeline. The goal was to build a 2-mile track, on par with the revised Indianapolis plan, in five months. They knew that at a minimum it had to have a state-of-the-art racing surface, grandstands, mechanic sheds, and a clubhouse. And they knew they wanted their first event to take place in early November. Since Indianapolis was aiming for their first auto race in August, they would have shortened the timeline if they could. But November was their best shot, and even that was asking a lot of their workforce.

By the end of June they had their construction contract in place. The crew—mostly comprised of unpaid prison labor—broke ground and began leveling the farmland and routing drainage of the various waterways that threaded through the landscape. The two-mile oval was designed with banked sides, enabling cars to take curves faster than they could on flat ground, similar to the Indianapolis plan.

Original blueprint showing parcels of land purchased from Hapeville residents, on file in the Candler Papers at the Rose Library Rare Papers Archive at Emory University

At the same time, Asa, Sr., continued to coordinate with the Atlanta business community to ensure the success of Auto Week, now scheduled for November 6-13, which would host a roster of automobile-themed events throughout downtown Atlanta while the races were running. This would include welcoming the arrival of participants in the New York to Atlanta Good Roads tour, a massive auto show, and parties galore. It would be, he claimed, a huge boon to Atlanta businesses. A sure-fire money maker for all.

Because Asa, Sr., was putting so much on the line he expected to control the decisions that went into the track’s costly construction and operation. But he also didn’t want to be personally liable for the potential losses if his son’s far-fetched scheme went awry. That meant he needed to form a new automobile club, his own business entity through which he could arrange the financing and management. In July of 1909, with a combined majority of shares, the two Asas launched the Atlanta Automobile Association, borrowing 2/3 of Ed Inman’s club’s original name.

Asa, Jr., was made President of the AAA, of course. He was the face of the organization and its speedway project, and rightfully the face of its success or failure. The board of directors, all men within Asa, Sr.’s inner circle, appointed an executive committee with complete authority in all things related to the track. This maneuver gave Asa, Sr., absolute control over the project. On the surface it appeared that Asa, Jr., was in charge, and evidence suggests that he was given a long lead to make decisions and guide the project. But at the end of the day it was Asa, Sr’s money, and since he’d been burned by his son’s poor business instinct before, he arranged things so that he would retain oversight. After all, Asa Griggs Candler, Sr., didn’t get rich by playing fast and loose with investments.

Through the end of May and beginning of June, Buddie and Ed Durant rallied for subscriptions to fully fund the track project. Once the AAA was established, they offered shares of the venture In exchange for investments, and donors received a certificate that specified their value.

Front of an AAA Certificate, on file in the Candler Papers at the Rose Library Rare Papers Archive at Emory University.

Reverse of an AAA certificate, on file in the Candler Papers at the Rose Library Rare Papers Archive at Emory University.

In the meantime, details emerged about all of the speedway’s planned features:

Location: 7 miles from the city center.

Total size: 290 acres.

Crowd capacity: 30,000 grandstand seats + open air viewing

Dimensions: 2-mile circumference, 100-foot width on the home stretch, 60-foot width on the banks and back stretch.

Banks: 10-foot rise to the outer edge, or 6 degrees, “shaped scientifically.”

Speedway village: Eleven farmhouses removed from the center of the oval to accommodate living and working quarters for racing teams and management, twelve or more fireproof garages, and a machine shop with power.

Additional buildings: clubhouse, groundskeeper quarters, complete waterworks and lighting plant, restaurant beneath the grandstand, ticket gates.

Garage details: For four cars each: two in the front, two in the rear. Drivers housed in rooms directly above.

Safety: Track bed built on a red earth base and covered in Augusta chert mixed with a special oil. No fences or rails necessary to protect spectators due to elevated grandstands. Safe passage for track officials provided by an overhead wire suspension bridge with a single walk that passed above the racing surface.

Of course, these details varied depending on the publication, and not all came to fruition. For example, the garage paddock was reduced and the units ultimately omitted the second floor apartments.

Promotional sketch for the 1909 races.

The details were made public well before the construction crews made any significant progress. This was the PR machine ramping up, building the necessary excitement to drive ticket sales to recoup the cost of the build. Another PR opportunity arose in July when automobile manufacturer Pope-Toledo gifted Buddie with a custom racer named The Merry Widow. Built for speed, the company claimed it would go two miles a minute without breaking a sweat. As one writer opined, “this car goes some.”

July 2, 1909, The Atlanta Georgian.

The first official Indianapolis automobile event ran in August of 1909, but safety concerns arising from the integrity of the compacted, oiled track surface cut the races short. A few days later another automobile race was held and made dramatic headlines when the track surface broke up, striking famed driver Louis Chevrolet in the face, and killing driver Wilfred Bourque and mechanician Harry Halcomb. On day three of the event a car careened into the crowd of spectators, killing two attendees and mechanic Claude Kellum. Then driver Bruce Keen hit a pothole and crashed into a bridge support.

The Atlanta Automobile Association leapt at the opportunity to use Indianapolis’ failures to its benefit. They promoted their scientifically designed track surface, safe spectator distance and banked turns in a promise that its first races would be nothing like the disastrous Indy event.

In September the AAA threw a barbecue at the still incomplete track and invited 500 of the wealthiest, most important members of the Atlanta community to attend. This wasn’t just any barbecue, this was a fundraiser. Word had gotten out that the project was well over budget and needed more funds. Rumors circulated that perhaps the AAA generally, and Buddie specifically, were in over their heads. To push back on this growing public perception, they completed their luxurious clubhouse and invited their guests to take the new track for a spin, or at least the section that was complete. They could tour the grandstands and see the concessions area, which of course served Coca Cola and absolutely no alcohol. Near-beer only, which one journalist noted was “not too near but near enough.” Another journalist noted wryly that the hard stuff wan’t too hard to come by, if one knew who to ask.

Atlanta Automobile Association Clubhouse, located at the Atlanta Speedway. Photo circa 1910.

ATlanta Automobile Association Clubhouse Reception Room, featuring fine wicker furniture. Photo circa 1910.

Of critical importance was the solicitation of subscriptions to help finish the paving of Stewart Avenue from the city center all the way out to the track. While the AAA had managed to lay an oiled bitumen surface up to the edge of the city, promising a dustless drive, the stretch of road from the city limits into the center of town was still unimproved. Many of Atlanta’s streets at that time were Belgium block from locally quarried granite. Better than dirt or macadam but not as smooth and modern as Auto Week deserved. The AAA needed funds to finish construction and rallied support for the route that would reach the track from in-town hotels and rail stations.

Behind the scenes Asa, Sr., was working with the Central-Georgia Railway Company to lay down tracks from Terminal Station in downtown Atlanta to the Speedway, promising that the investment would pay off nicely during Auto Week. Business correspondences on file at the Emory University Rare Papers Archive reveal a tense, dubious relationship between the rail company and the AAA, suggesting that while local businesses got on board with the plans for Automobile Week, they weren’t all necessarily convinced that it would be a success.

In spite of this, Asa, Sr., continued to gather as much support as he could from the community, raising donations to build up the city’s infrastructure to support the influx of tourists. As the founder of the city’s Chamber of Commerce, the man had a knack for bringing businessmen together and pooling money to make more money. It’s said that for every dollar Asa Candler, Sr., made, he made another dollar for someone else. Plenty of Atlantans had profited by going along with the elder Asa in other endeavors, so the community put itself on the line to follow him toward big tourism dollars.

In September, Vanderbilt Cup race planning went into full swing, and Buddie Candler and Ed Durant traveled to New York to do some networking. They spread the word about the Atlanta Speedway, and they cozied up to famous drivers in the hopes of recruiting the best men for their inaugural race. They also announced that the Atlanta races would offer up to $25,000 in prizes, as well as a trophy worth $10,000. On October 19, 1909, the Indianapolis News reported the following:

“The $10,000 trophy which will be contested for during the meet in many respects resembles the Wheeler-Schebler trophy at the recent Indianapolis Meet.

It is considered by experts and judges of high art to be the most magnificent automobile trophy ever designed. The trophy is six feet high and made of solid silver. It is a representation of the mythological god of speed, Atlanta, running away with the Greek goddess, Atalanta.

Atlanta has outspread wings to assist him in his speed, and the maiden he holds in his arms holds the laurel leaves of victory in one hand and an automobile of gold in the other. Around the base of the trophy is the picture of an automobile race, below which are the seal of Atlanta and the state of Georgia.”

Automotive Age, Vol 21, 1909

While this was going on, newspapers were starting to spread the word that the racetrack project had gone $5,000 over budget (more than $130k in 2019 dollars).

And then more gossip emerged. Rumors spread that Ed Inman’s Fulton County Automobile Club and the Atlanta Automobile Association would merge. In fact, the primary rumor was that the AAA asked FCAC to absorb them. This was, of course, anathema to Buddie’s sense of superiority. He insisted that there was no way the two clubs would merge. And besides, he claimed the FCAC approached the AAA, not the other way around. Ed Inman gave an even-handed statement, claiming he didn’t care either way, and if the club members voted to merge he would not block the move. Buddie, on the other hand, emphatically insisted that the FCAC made “repeated” appeals for the AAA to merge with them. He also claimed to be a member of both clubs, and as such saw no point in the merger. Finally, in a pattern that played out later in his life, he claimed the premature press soured the whole deal anyway, which was a bit contradictory. If there was no deal, how could the papers sour it? This logic arose again in the mid-1920s during the great Mule Mart drama, which is covered in the Real Estate section.

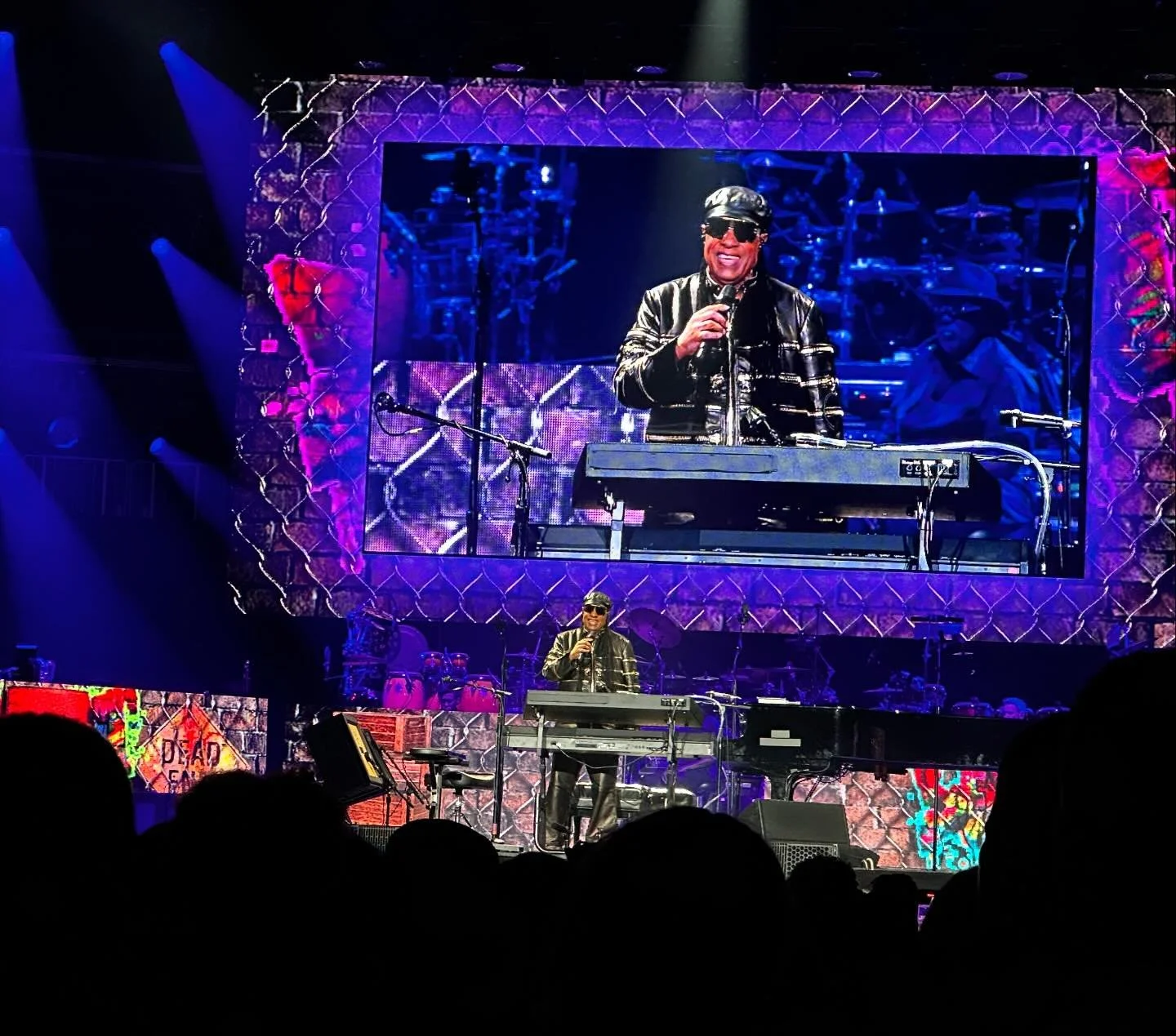

On October 23, 1909, the AAA declared the track complete and celebrated with an exhibition race. They recruited big names to participate, including legendary driver Barney Oldfield and George Robertson. And given what’s known about Barney Oldfield’s rates, they surely paid top dollar for his participation. Buddie’s pal Ed Durant set the state-wide amateur speed record in his Renault. Buddie’s Pope Toledo, The Merry Widow, was driven by a young man named Florence Michael, who adopted the stage name Louis Cliquot for his racing debut.

Motor Age, October 1909

Motor Age, October 1909

On October 30, the Vanderbilt Cup race drew big crowds and the biggest names in auto racing. When the race was over those same big-name racers turned right back around and headed south to Atlanta once again. Auto Week was about to begin. On November 5 an exhibition race entertained the early birds who arrived in Atlanta a week before the festivities kicked off on the 9th. Famed female driver Joan Cuneo took her car out onto the track and handily defeated the competition as she ran the 2-mile circuit in 1 minute, 45 seconds. On November 6th the first cars in the New York to Atlanta Good Roads Tour arrived, and were greeted by an exuberant welcome party who threw a celebration in their honor. The crowd was growing every day, and the stakes were so high that Buddie and Ed Durant took out a $100k insurance policy to protect their investment in case of rain.

And finally, on November 9th, the races began. The Atlanta Speedway was open for business. More than 150,000 racing enthusiasts attended the inaugural event, and the auto show in downtown went off without a hitch. When the week of festivities wrapped, the Atlanta Journal had this to say:

“With the completion of the speedway races in the afternoon and the closing of the automobile show last night, a new page in Atlanta’s history was written. The page will stand out in bold relief when the special events it chronicles are compared with others among the many notable achievements of the city.

The success of the whole affair may be summed up in the statement that Atlanta had something to offer, and offered it in the best possible manner. No other city in the country twice Atlanta’s size has ever put on anything in the entertainment line half so big nor nearly so successful as automobile week.”

With such high praise and big turn-out, it seems like a given that the event was a rousing success. Asa, Jr.,’s vision paid off and Asa, Sr.’s investment was well placed.

Right?

Well, not exactly. Trouble loomed from the very start, and although on the surface the endeavor was a successful one, the Atlanta Speedway’s failure was an inevitability. For all of the efforts to bury Indianapolis, Indy’s track still exists and Atlanta’s track barely survived two seasons. Under scrutiny, the reason from the failure becomes quite apparent, and it all leads back to Buddie Candler.

The Birth of the Atlanta Speedway Gallery

Source: Motor age, Oct 1909

Source: Motor Age, October 1909

Asa Candler, Jr., (L) and Edward Durant (R). Source: Motor Age, October 1909

Exhibition Race Results, October 24, 1909, The Atlanta Constitution

Inaugural Races schedule, November 8, 1909, The Atlanta Georgian

November 6, 1909, The Atlanta Constitution

Atlanta Speedway 1909 Race Photos

Attendee parking area

Entry gate turnstiles

Backside of the grandstand featuring food stalls and restaurant

Backside of the grandstand featuring food stalls and restaurant

Grandstands viewed from the track

Track viewed from the grandstands

Starting line-up

Starting line-up

Open air seating

Special viewing area for attendees watching from their cars

Timing booth

Timing equipment

Garage paddock

Garage paddock

Pit crew

Pit Crew

Buddie behind the wheel

Buddie (L) with other race officials

Buddue (r) with Louis Chevrolet

Buddie (2nd from right) with The Merry Widow and his driver

Buddie (L) with another race official

Buddie (4th from right) with other race officials

Buddie (2nd from right) with other race officials in front of the timing stand

Buddie (L) with other race officials and Grandstand in the background

Note: Help me identify these racers! Please use the form on the contact page to send me names if you recognize any of the gentlemen in the following photos.

Louis A Disbrow driving a Rainier

Driver with Simplex crew

Unidentified drivers

Driver Joe Matson

Unidentified Simplex Driver

Louis schweitzer driving an Atlas (confirmation pending)

Charles Basle (L) and unidentified driver

Unidentified drivers

Unidentifed Drivers

Unidentified Drivers

Louis Strang driving a Fiat

Unidentified driver

unidentified driver

Unidentified driver

Unidentified Driver drinking coca cola

George Robertson drinking coca cola

Driver Hugh “Juddy” Kilpatrick (L)

Unidentified drivers

Harry Stillman, driving a marmon

Unidentified driver and passengers

Atlanta’s National Auto Week, Motor Age, Nov 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Main Floor, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Entrance to Auditorium, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Main Aisle Toward Entrance, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Packard Motor Car Co. Exhibit, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Pierce-Arrow Exhibit, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show, Dayton Motor Car Co., 1910 Stoddard Types, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Premier Motor Manufacturing Co., Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Chalmers-Detroit Motor Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Winton Motor Carriage Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Stearns Chassis and Car, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Peerless Motor Car Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Pope-Hartford Exhibit, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Woods Motor Vehicle Company Electric Cars, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Mitchell Motor Car Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Stevens-Duryea Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show, REO Motor Car Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Thomas B. Jeffery Company, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: Locomobile Company of America, Auto Week, November 1909

Atlanta Auto Show: White Company Gasoline and Steam Exhibit, Auto Week, November 1909

Speedway Article Written by Asa Candler, Jr.

“How Atlanta’s Great Speedway was Built

By Asa G. Candler, Jr., President of the Atlanta Automobile Association

The building of the Atlanta Speedway and the organization of the Atlanta Automobile Association was not in any sense the outcome of a long-contemplated plan. Instead it was all thought out in a few minutes’ time, and once the start was made, not a moment was lost in completing the work.

One afternoon Edward M. Durant, of Atlanta, and myself were near Hapeville, a small town adjacent to Atlanta. We had made the trip out on business far remote from that of building an automobile track. As we passed a large tract of land the identical idea seemed to occur to both of us at the same time. The idea was spontaneous, one might say, and the very instant we began discussing the question it was settled in our minds that we would start the work at once.

The land we had seen was not all in one parcel, but several scattered pieces, and in order to secure what was needed we had to make a number of trades. This was done, and then work was started on the plant.

In the meantime the Atlanta Automobile Association was organized, and the land taken over by that organization. Officers were selected by the stockholders, and they were kind enough to make me president. Mr. Durant was elected secretary, and right here let me say that he has been a most valuable man in every detail of the great undertaking.

After the association was organized the task of getting the grounds arranged and having the course laid out was placed in the hands of Mr. Durant and myself. We did not want to lose any time in having the work completed and set a time for it to be finished. We decided to have the first meet on November 9, and continue up to and including the 13th of that month. We consulted with a number of contractors and they declined to undertake the job, for we were not ready to begin until July. The idea had occurred to us in June, and after getting the needed land we had no time to spare,

Many experts looked over the situation and declared it was impossible to complete the task in the time we had to give them. They would figure a while, and then with a shake of the head tell us it was not in the power of man to accomplish the undertaking. Just as it looked as if we would have to take the contract over and do the work personally, we found a firm that was willing to take a chance. It did not take us long to come to terms, and work began almost the day the contract was signed.

We got little encouragement from any one save our stockholders when it came to discussing the time for the opening. Nearly every one declared we had undertaken too big a job for the number of days we had in which to work. We were determined, however, not to break our promise, and soon had a night force working. In order to do this a special system of lights was put in. This was done, and there was no stop except when the weather became so bad there was no chance to go ahead. The men who took our contract were experts. They had the facilities with which to carry out their part of the agreement, and did so.

The plan was not one for the purpose simply of making money. It was intended to advertise Atlanta, to show to the world that the claims made for the city are not idle ones. We wanted the best plant in the country, and I think we have it. But we have just begun. The grounds are to be beautified in every way possible, and we will not stop there either.

The recent try-outs given the course by some of the greatest drivers of automobiles in the world have served to show how near perfection is the course. There was not a complaint, not a suggestion to come from any of the men who drove over the course on Saturday, October 23. but there was praise from all of them.

The Atlanta Automobile Association is composed of leading business and professional men of Atlanta. The association is going to foster automobile racing on a high plane. Everything will be done to advance the sport and to protect it. There is to be no shamming. There is not a dollar of stock in the association owned by manufacturers of automobiles or of kindred enterprises. No make of machine will ever be favored by the association to the injury or inconvenience of another. The association is free from obligations, and its only object is to give the best possible entertainment and to establish itself in the world of sports as one of the great national organizations.”