Music Hall, Briarcliff Mansion, at the time of sale in 1947.

In 1925 Asa Candler, Jr., broke ground on his first renovation of his newly completed mansion. He added a music hall to the front of the house, which was intended to house a great pipe organ. The music hall is currently known as DeOvies hall, but that name came along much later, after the house was sold and used by the state for alcoholism rehabilitation.

In-home pipe organs were popular among the very wealthy during the Gilded Age. This symbol of wealth was something that stuck in Asa Candler, Sr.’s, head, so when he built his mansion on Ponce de Leon Ave. he included an Aeolian pipe organ that ran through the house’s ductwork with grills in the main courtyard and in the ceiling rosette of the music room.

When his oldest son, Charles Howard Candler, built Callanwolde, he adopted his father’s somewhat old fashioned vision of status and purchased a $48k Aeolian organ of his own, with 55 ranks, 147 stops and 3,742 pipes. The Callanwolde organ pipes appear around the foyer entryway, in the ceiling rosette at the top of the grand staircase, and in two hidden ceiling panels elsewhere in the home. His organ was bigger and grander than his father’s.

So Buddie, being the superlative type, had to top them both. With 88 ranks, 187 stops and 4,764 pipes, his Aeolian organ was the largest in Georgia and the eighth largest the company ever built. The majority of the pipe work, which included a pair of 32’ stops, resided behind an ornamental screen at the north end of the music hall. Ductwork ran through the house and delivered wind to a second set of pipes in the solarium on the southwest corner of the house. The original price was more than $94k for the main organ and another $9k for the solarium organ.

Rumor has it that there was a smaller organ in the third floor ballroom, but that is unconfirmed. No evidence exists aside from anecdotal claims that a second ballroom organ was installed at Briarcliff. All three of the confirmed Candler organs had the ability to be played automatically via scrolls, similar to a player piano.

The instrument’s inaugural performance was a performance by organist Palmer Christian, and it was broadcast on newly launched radio station WSB. Throughout the 20s and 30s Buddie, his first wife Helen, and his second wife Florence hosted performances in their home, and often hosted meetings of the Organists’ Guild. The construction of the music hall abutted the second floor master suite, so they built out a private listening box where they could enjoy performances above the heads of their guests.

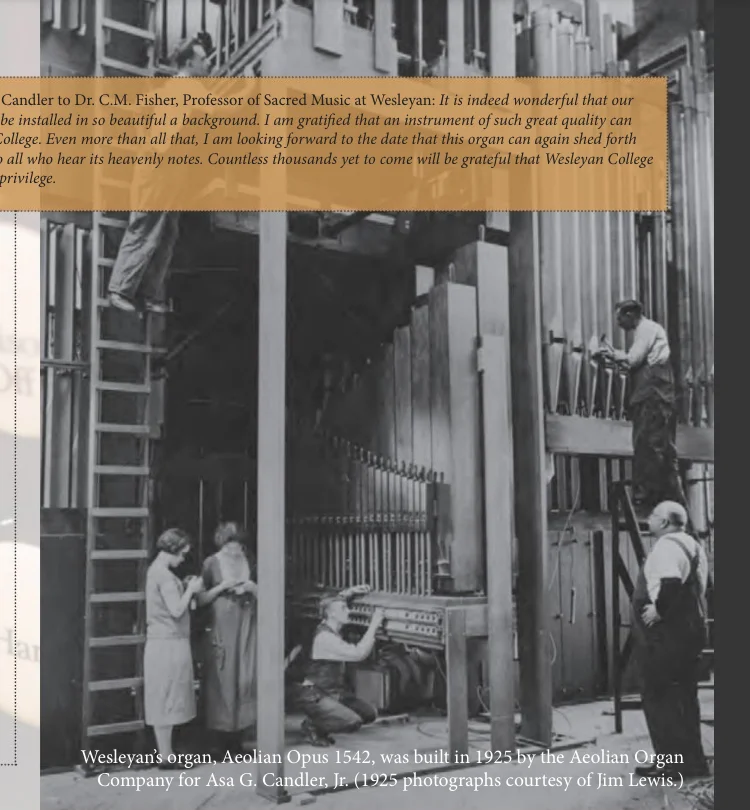

When Buddie neared the end of his life and started liquidating his assets, the organ was appraised and then sold/gifted in 1952 to Wesleyan College in Macon, GA. Bishop Arthur J. Moore, who was friends with Asa, Jr., convinced the school to accept it. At that point it was appraised by PricewaterhouseCoopers in its disassembled state at $50k in value. It came with a new console and components of the original console, and when it was installed in 1958 the school discovered that the echo organ had acquired water damage while in storage, so they had to discard 10 ranks. The remaining instrument was in working order, but rebuilding and installation at the college cost $40k. The Methodist church donated $20k towards restoration.

Florence attended the dedication in 1958. Atlanta organist and family friend Virgil Fox performed at the dedication. Rumor has it that Buddie’s children felt Virgil Fox had built his musical career off of the Briarcliff organ and didn’t appreciate its relocation or its dedication. Purely anecdotal claim, of course.

Years went by and the organ fell into disrepair. In 1989 it underwent a minor restoration, and then in 2009 a major restoration effort brought it back to performance quality. The instrument is now designated the Goodwyn-Candler-Panoz Organ and is in working condition at the Porter Fine Arts Building of Wesleyan College.

Most of the components of this organ were originally installed in Briarcliff Mansion in Atlanta, GA. Owned by Asa Candler, Jr., second son of Coca Cola founder Asa Griggs Candler, it was donated/sold to Wesleyan College in 1952, installed in 1958, and completely restored in 2009. It is now designated the Goodwyn-Candler-Panoz Organ and is in fully working condition.

Briarcliff’s sixteen sets of solarium pipes followed a different path. Buddie separated them from the main organ and had them installed in the Florence Candler Memorial Chapel at Westview Cemetery’s Mausoleum sometime around its dedication in 1949. The organ remained playable for a couple of decades, then fell into disrepair. They were sold to Reverend Roy O. McClain, who took them home to South Carolina and donated them to Charleston Southern University. The solarium organ was installed at Lightsey Chapel by the Moller Organ Company, who added enough additional pipes to round out a full auditorium-scaled instrument. The organ was functional for many years before falling into disrepair. Then in 1989 Hurricane Hugo pummeled the Charleston area and caused widespread destruction throughout the city, including the CSU campus. Lightsey Auditorium was damaged and the organ was silenced.

For decades the instrument remained silent, with no funding allocated for its restoration. As it sat above the wings of the auditorium stage, gravity weighed heavily on the grand pipes, bending them out of shape and further diminishing any prospect of repair.

But in 2018 the college approved a proposal by Horton School of Music staff to take on the restoration project without funding, doing the painstaking repair work in their free time. As of August 2018 the organ is now playable, with only a few remaining pipes in the stage-right loft still too damaged to pass sound. Although the Aeolian company did not hallmark its pipes, materials and techniques evident in some of the ranks in the stage-left loft indicate that some of the Briarcliff solarium organ may still live on.

Restored in 2018, the organ at CSU was originally part of an Aeolian residential organ that was installed in the solarium at Briarcliff Mansion in Atlanta, GA. Owned by Asa Candler, Jr., second son of Coca Cola founder Asa Griggs Candler, the solarium organ was moved in the late 1940s to the chapel at Westview Cemetery and then given to Rev. Roy O. McClain. McClain took the organ to South Carolina, where it became a donation to CSU.

Special thank you to:

Michael McGhee, D.M., Associate Professor of Music , Wesleyan College

J. Matthew Swingle, Adjunct Prof. of Music, Band Administrator, Horton School of Music, Charleston Southern University

Music Hall & Organ Gallery

View of Briarcliff organ installation.

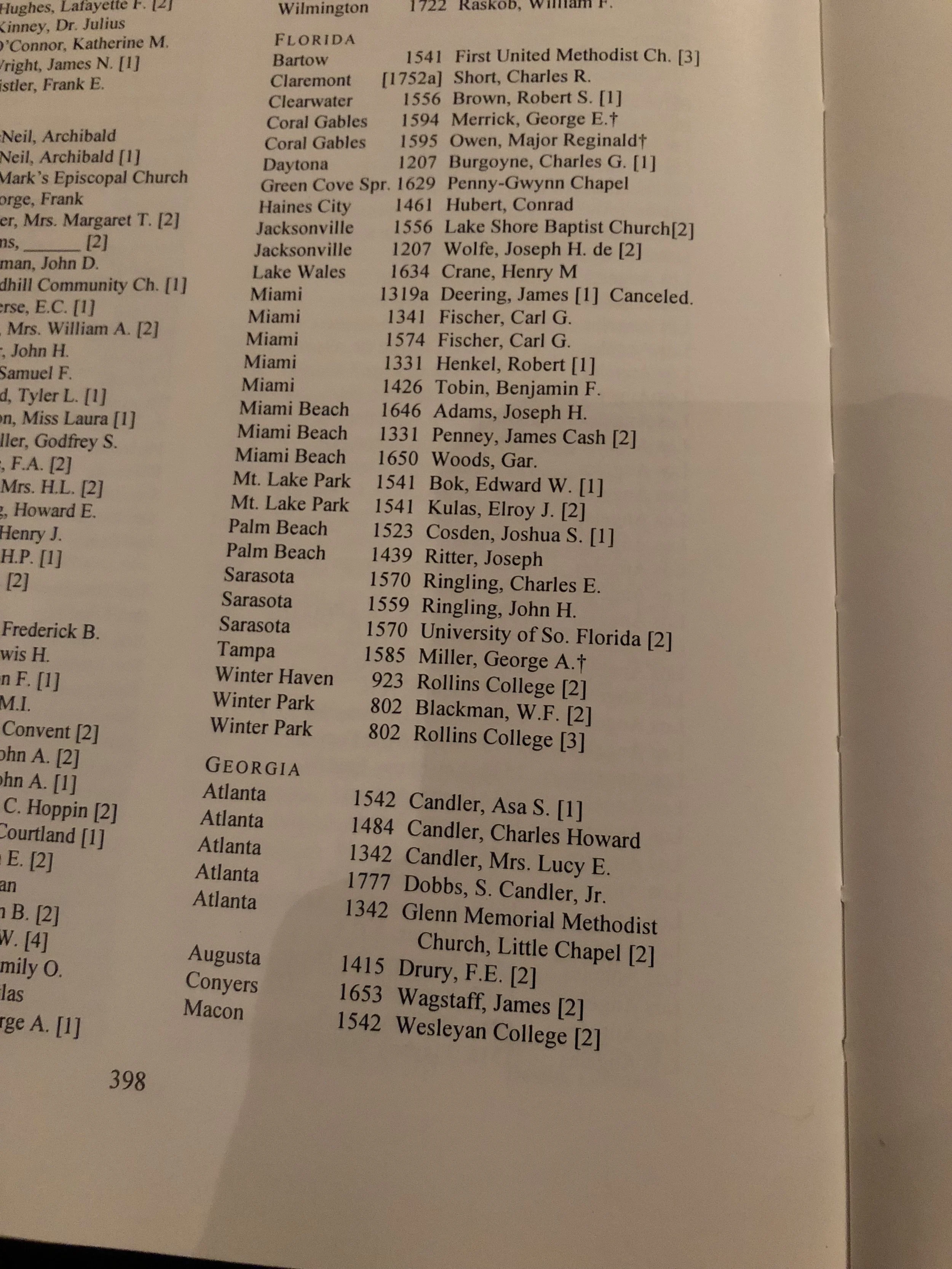

Aeolian Organ Catalog

Aeolian Organ Catalog. The listing shows that Asa, JR., (incorrectly listed as Asa S.) owned the instrument with catalog number 1542. The 1542 organ is also listed at Wesleyan. Asa, Sr.’s organ, number 1342 went to the Glenn Memorial Methodist Church, Little Chapel. It no longer resides and the current location of the pipes, if they were not destroyed, is unknown.

Current view of the Briarcliff scroll cabinet at Wesleyan College in MAcon, GA.

Original Contract for the BRiarcliff Organ.

Original Briarcliff Organ contract.

A component of the original Briarcliff console showing the Solarium controls.

Original Briarcliff organ pipes, installed at Wesleyan College in Macon, GA.

View of original BRiarcliff organ pipes, installed at Wesleyan College in Macon, GA.

Original Briarcliff organ pipes, installed at Wesleyan College in Macon, GA.

Organ loft at Charleston Southern University, likely containing original Briarcliff Solarium organ pipes.

Likely pipes from the BRiarcliff solarium organ, Charleston Southern University.

Textue and finish indicative of the kind of production style associated with the time period in which the Aeolian pipes were produced. Charleston Southern University.

Internal components of a possible Briarcliff Solarium pipe. Charleston Southern University.

Internal components of a possible Briarcliff Solarium pipe. Charleston Southern University.