Atlanta’s Hotel Ansley, which Asa Candler, Jr., owned and managed for many years.

Asa Candler, Jr., was a real estate man, first and foremost. According to his obituary, he owned as many as 33 apartment buildings and several hotels throughout his life. While a full accounting of his portfolio is not consolidated anywhere, compiled documentation yields insights into his holdings. Although he was not necessarily responsible for the build of the following, he is confirmed to have owned and/or managed on behalf of the Candler Investment Company or Briarcliff Incorporated:

The Atlanta Speedway (eventually Candler Field, then Hartsfield-Jackson Airport)

The Atlanta Union Stock Yards (formerly Miller Union Stock Yards)

He also owned land that he sold to the government to expand Camp Gordon in the WWI era. And he was one of the original fundraising and real estate advisors for the Shriners’ Yaarab Temple that eventually became the fabulous Fox Theater.

In this section I’ll share a few stories that came out of his Real Estate doings.

The Hotel Ansley

In August of 1919 Buddie and his siblings each made $5mm (more than $70mm in 2019 dollars) from the sale of Coca Cola. As soon as Buddie had his cash in hand he started burning through it as quickly as he could. He would go on to make many massive purchases, both personal and in real estate. He would sometimes profit, he would sometimes lose money.

Just before the Coca Cola deal went through he made his first big move when he announced a $2mm expansion to the existing Ansley Hotel, of which he was the lessor, and the resulting property would be valued at more than $4mm. He claimed it would be the largest hotel in the Southeast, with 800 rooms and a massive connected lobby. The project never happened. It was outrageous in scope, and two years later Buddie moved on without fanfare. In March of 1921, an announcement in the local newspaper noted that Louis J. Dinkler had taken over the lease and would manage the hotel, effective immediately. The Hotel Ansley was Buddie’s greatest phantom project. He didn’t allow any future projects to fade away like phantoms.

Macy’s

In 1924 he orchestrated a deal to bring the very first Macy’s store to Atlanta in his typical over-the-top, grandiose way. The 1924 tour of Atlanta by Nathan Straus, then Vice President of Macy’s, spawned numerous rumors that a store would open, a rumor that was neither confirmed nor denied by Mr. Straus. Buddie himself drove Mr. Straus around and showed him all of the large, wealthy estates of the city to convince him that the store would have no troubles drawing customers. By 1925 they were ready to announce that they would build out a $6mm plan, consisting of six floors and a basement theater. Buddie was hailed as a patriot, a visionary, and a key player in convincing major businesses like Macy’s and Lowes Theaters to see Atlanta’s value in their broader business plans. In 1927, as the Macy’s build neared completion, Mr. Straus returned for an inspection and gave the following statement:

“It is a material and unquestioned tribute to Asa G. Candler, Jr., that the work has gone along so spiritedly. Whle I am not at liberty to announce any definite date for the opening, I must say that I can hardly wait until that time to see how Atlanta takes to the new store. ...We have a peculiar faith in Atlanta. In building the structure Mr. Candler has done his part.”

On March 21, 1927, the store opened in downtown Atlanta on Peachtree St. under the name Davidson-Paxton’s. It was the largest department store south of Philadelphia, with the largest store window expanse in the country. Of course it was, with Buddie running the project. He lived for superlatives.

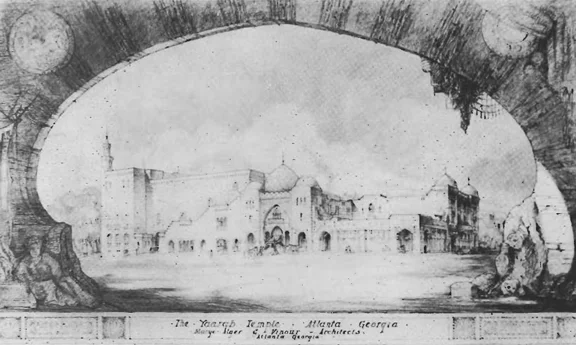

The Fox Theater

In 1925 the Shriners of the Yaarab Temple, of which Buddie was a member, decided they’d outgrown their meeting space. They needed to build something new, and that meant real estate doings. Enter Asa Candler, Jr., who took a place of leadership on the financial team, known as the “special loan committee.” At a group meeting on September 9, 1925, Buddie took to the podium and gave a rousing speech along with his brother-in-law and past Potentate Henry Heinz to present what Henry claimed was, “the most practical, the most feasible, and in all ways the finest financing plan.”

In October of 1925 the Yaarab Temple Shriners celebrated the success of their drive to raise $1mm to break ground on their new building. The plan was to build a meeting space for their organization, along with a great auditorium which could be rented out and serve as an income generator for the club. Chairman Adams announced on behalf of Potentate Brown that the auditorium would be named the Asa G. Candler, Sr., Memorial Auditorium. The inclusion of “Sr.” is interesting. To the city of Atlanta, Asa Candler was Asa Candler. His son was Asa Candler, Jr. It’s rare to find Asa, Sr., referred to as such unless it’s in direct context with his son. Given that Asa, Jr., William and Henry Heinz were on the committee, it seems likely that they suggested adding the suffix. Buddie certainly would have seen himself as prominent enough to necessitate the distinguishing detail.

The fundraising efforts brought the group within reach of their goal, coming in around $900k. Asa, Sr., donated $1k personally to help close the remaining gap. The organization then asked for individual members to pledge donations, and Buddie pledged $10k of his own money on top of the $10k he’d already given.

Original illustration of the new Yaarab Temple that would eventually become the Fox Theater

He spent 1926 riding around with high-ranking Shriners in his private luxury railcar, rubbing elbows with influential brothers. He was listed as the temples chief of staff, although he never progressed past the ranking of Noble. The temple project hired an architectural firm in 1927 and immediately discovered that the scope of their plans far exceeded their fundraising. They negotiated a deal with Fox Films Corp to share the cost burden and gave Fox a 21-year lease. That agreement enabled them to break ground and lay the cornerstone in 1928, but they quickly found themselves in financial crisis once again. They revised their plans and continued plowing forward toward completion.

In 1929 the Great Depression put pressure on the project again, but by now they were in too deep to walk away. They eliminated some of the planned details, like a gymnasium, and came up with workarounds when the economic slump made construction materials hard to come by. The theater opened on Christmas day, 1929, and the mosque portion was dedicated by the Shriners on New Year’s Day, 1930.

In 1932 a small blurb appeared in the Atlanta Constitution:

“Judgment given the Shrine Building Company against Asa G. Candler, Jr. for $10,000 on an allegation that Candler refused to pay a stock subscription for the Shrine Mosque was upheld by the court of appeals in a decision handed down on Friday.”

It raises the question, what happened between the pledge of $10k in 1925 and the calling of that debt?

I first heard of the history of the Fox Theater years ago on a history tour. When I ran across the information that Buddie was a Shriner during the period when the Fox was constructed and remembered how the financing unravelled in the face of an overblown proposal, I suspected he was involved. And when I found confirmation that he was a leader of the financing committee, it all made sense. It had his fingerprints all over it. Grandiose ideas with good-on-paper proposals that unraveled financially once set in motion were Buddie’s specialty. The Atlanta Speedway, the Ansley Hotel expansion, the Candler Floating School, The Briarcliff Zoological Park, the West View Mausoleum and Abbey, all of these ideas followed the same pattern as the Fox. Unfortunately the archivists at the Fox Theater don’t have sufficient documentation about the individuals involved in the project to confirm how much of a guiding hand Buddie had in its construction. Attempts to contact the current Yaarab Temple organization have not been successful.

Cotton and Cattle

In 1924, around the time that Buddie was giving the Macy’s bigwigs a personal tour of Atlanta’s finest neighborhoods, he also worked on a deal to charter a $2.5mm cotton warehouse system named the Southeastern Compress and Warehouse Company in partnership with William H. Glenn, brother-in-law of Buddie’s older brother Howard. The system included the massive Candler Warehouse that Asa, Sr., built in 1914 and was one of the sites involved in the Great Fire of 1917.

That same year, 1924, he bought controlling interest in a failing livestock yard, the Miller Union Stock Yard. He and William H. White, Jr., of the White Provision Company, a large meat processing concern, went in on the deal together and planned to expand it to become the dominant force in livestock auctioning in the Southeast. Combining a dominance in cotton and a dominance in livestock would put Buddie at the forefront of an Atlantan agriculture industry boom. He and Mr. White renamed the business and incorporated as the Atlanta Union Stock Yards.

In July of that year Buddie shot his mouth off to the press about a potential merger between Richmond-based Southern Stockyards and the Memphis-based Maxwell Brothers. Buddie was now at the helm of the newly-established Atlanta Union Stock Yards, and rumor had it that the merger between twin businessmen James and Thomas Smyth and the Maxwell brothers would result in Atlanta becoming the central clearinghouse of livestock for the Southeast, just as Buddie had envisioned. In his effort to boost Atlanta’s image as the NYC of the South, he provided the following statement without approval from either the Smyths or the Maxwells:

“We have completed all preliminary arrangements whereby the Atlanta union Stock Yards will become the headquarters for two of America’s largest horse and mule firms, and these companies—Maxwell Brothers of Memphis and St. Louis, and Smyth Brothers, of Richmond, will open America’s greatest mule auction in Atlanta September 1.

We have had workmen busily engaged for some time rehabilitating our barns and installing adequate facilities for handling this increased business. Everything will be in readiness for the opening day, and the many buyers and sellers attending these big sales will find one of the best equipped yards in the country. Before closing with us, the two firms investigated every claim made in favor of Atlanta as the logical distributing point for the southeast. Not only did they find every statement fully justified, but that Georgia’s 1924 agricultural condition doubless will enable her farmers to restock their farms with sorely needed work animals.

The bringing to Atlanta of these two firms will in no way interfere with our increasing volume of cattle, hogs and sheep. These meat animals are yarded and marketed in a separate section of the yards, where all modern facilities have been installed.

When I associated myself with W. H. White, Jr., president of the White Provision Company, in the purchase of the stock yards formerly operated by the Miller Union Stock Yards, we announced our intention of making Atlanta the greatest livestock market of the south. This is but one phase of our plans, and subsequent developments will be announced as they are perfected.”

Since Buddie had a five-year contract with the Smyths and business with the Maxwells already, he assumed the newly merged business would certainly lease more space from his stock yard, raising the value of Atlanta Union Stock Yard, Inc. William White was hard at work securing agreements with the Smyths and Maxwells, as his provision plant would benefit greatly from increased livestock business, if not directly from the horse and mule trade. Buddie’s announcement was premature, but because he knew about the ongoing conversations with his business partner, in his mind it was as good as signed and sealed. Why not pump up their public image and drum up advance business by creating excitement in the region?

In response to Buddie’s announcement, Thomas Smyth made a public statement, saying that Southern Stockyards intended to open an Atlanta branch for two years only, and no merger was on the table. Buddie replied to his denial, saying he held a five-year lease belonging to the Smyth brothers for quarters on the grounds of the Atlanta Union Stock Yard and that he was 100% certain that the Smyths and the Maxwells had signed a contract.

That was when William White, whose couldn’t afford for his business relationships with both the Smyths and the Maxwells to be burned by Buddie’s missteps, stepped in to clarify that there was no merger. He said both companies independently intended to move their headquarters to Atlanta and operate independently. He provided the following statement about his impulsive business partner:

“Premature publication in an afternoon newspaper of this matter has proved greatly embarrassing to me. I had taken steps to secure cooperation of all Atlanta newspapers in handling details of the important transactions only after final consummation and approval of the plans, and ill-advised publication has caused me great distress.”

Buddie countered once again by pointing out that there was no need for secrecy, since he already held business with both concerns and they had both expressed “great satisfaction” with his plant and shipping facilities. He portrayed the merger and relocation of headquarters as recognition that Atlanta was home to one of the greatest natural livestock centers in the country. And combined with Atlanta’s dominance in the cotton sector, thanks largely to the immense Candler Warehouse, the move would provide a much-needed economic boost to the region, which had been hit hard by partial crop failures in 1920 and an influx of boll weevils.

When the dust settled it turned out Buddie was partially correct. The Smyth Brothers and the Maxwell Brothers moved their headquarters to Atlanta, but did not merge. And the PR faux pas wasn’t important enough to prevent them from leasing spacious quarters from the Atlanta Union Stock Yards. He was even right about the date. By September 3, 1924, both companies had relocated and were already starting to auction off their livestock in large numbers.

But it seems a rift now existed between William White and Asa Candler, Jr. In December of 1924 White went to a livestock event in Chicago with Buddie’s consent. Then, while he was out of town, Buddie called a meeting of the board of directors without him, and together they voted White out of the leadership of White Provisions Company, which had remained under White’s management as a subsidiary of Atlanta Union Stock Yards. Buddie was then elected by the board as President in his place. The situation has shades of the 1909 drama with Edward Durant following the inaugural Atlanta Speedway Races. That business relationship falling out also resulted in a secret December board of directors meetings that ousted a company leader. History repeats itself, and Asa Jr. cycles.

Business skyrocketed over the next few years and Buddie significantly expanded his real estate holdings. By 1925 he and his brother Walter owned 5,000 sq. ft. of property worth more than $3mm along Peachtree St. In January of 1928 the Atlanta Union Stock Yards announced that business was so booming that they had more demand for animals than they could find suppliers for. Tremendous growth had paid off handsomely, or so it would seem.

So when Buddie announced in May of 1928 that he would be repurposing the land that the Atlanta Union Stock Yards occupied for “other purposes,” everyone was surprised. The Smyth Brothers promised that there would be no interruption in service, they would simply find or build new barns. Other tenants promised that the change wouldn’t affect their businesses, either. But it seems clear that behind the scenes there was some consternation about the unanticipated announcement.

By August of 1928 Buddie found himself in court, the subject of a lawsuit filed by the Smyth brothers for evicting them when they still had three years left on their lease. Buddie’s only statement was that the tenants were “not paying in its present capacity.” They went back and forth and the case climbed through the court system as he fought it to the bitter end. He always fought lawsuits to the bitter end. In March of 1929 the Georgia Supreme Court reversed an injunction and affirmed Buddie’s right to refuse to renew their lease.

Buddie the Phoenix: Following the Real Estate Cycle

It was all sound and no fury. In June of 1929 Atlanta Union Stock Yards made a call for redemption of all issued bonds and then…. nothing. The stock yard didn’t go anywhere. It continued operating just as it had. The land wasn’t repurposed. Nothing dramatic happened. So what was the fight between Buddie and the Smyths all about? He grappled over money with the Smyths and the Shiners at the same time.

Asa Candler, Jr.’s, life was an ongoing cycle of soaring highs and crashing lows. Like the mythical phoenix he would financially self-immolate every now and then and emerge from the ashes flush with cash and ready to start spending again. At the start of a burning phase he would often make rash, impetuous decisions and announce them to the public without fully thinking them through. This time it was the closure of the stock yards. In 1909 it was his departure from the Atlanta Speedway debacle. In 1933 it was the imminent closure of his private zoo. In 1949 he flirted with this pattern by ordering a stop to all lawn care at West View Cemetery. It was a strange flex, showing off his ability to kill a money-making venture without a second thought.

So why did he flex in 1928? What else was going on? Well, in February 1927 Buddie’s wife of 27 years passed away. In November he remarried under intense public scrutiny. Also in November his father, Asa G. Candler, Sr., suffered a debilitating stroke and went into the hospital. Asa, Sr’s prognosis looked grim, and was an unexpected and ignoble turn for the man who had meant so much to the Atlanta community at large.

Buddie spent the next several months sailing his private yacht in the waters between Florida and Cuba, as well as taking steamliners across the ocean to distant countries. He was always on the move, and between 1927 and 1929 he traveled more than any other time in his life.

In April of 1928 his personal yacht was boarded and searched by U.S. Customs agents, who found a significant load of liquor on board as the ship headed back into U.S. waters. This was a big no-no, given that this was peak Prohibition and bootlegging from Cuba was a real problem. The timing of the following burn cycle raises the question of whether Buddie had to pay to avoid consequences from importing booze illegally. It was no secret that the Candlers paid to make personal legal problems disappear.

Right after the search and seizure event Buddie announced in May that he would be evicting his tenants from the Atlanta Union Stock Yard and repurposing/selling the property for an unspecified purpose. In early June he negotiated with the city of Atlanta to pony up and purchase Candler Field once and for all. In late June of 1928 he sold his controlling interest in Southeastern Compress and Warehouse for a cash consideration of $4mm. This deal included the massive, 40-acre Candler Warehouse, as well as many other facilities.

Selling his interest in Candler Warehouse in 1928 was a big deal. The 40-acre, 1.25mm sq. ft. facility on Stewart Avenue had been a major piece of the Candler portfolio for many years, but Buddie claimed the sale was purely an investment decision. But it was an investment decision to sell off a major business started by his father as he languished in a hospital, progressing slowly but surely toward his end.

In January of 1929 he left on another trip to Egypt and the Mediterranean. In February his cousin Asa W. Candler passed away. On March 12 Asa, Sr., passed away. Buddie was overseas when it happened. After that a few things set in motion in 1928 in the midst of his burn phase wrapped up, including the court case against the Smyth brothers, the finalization of the sale of Candler Field for $94k—negotiated down from the asking price of $100k—and the successful recall of bonds for the Atlanta Union Stock Yard. In May of 1930 Buddie acquired a 50-year leasehold on the Robert Fulton Hotel for $800k and sold the Atlanta Union Stock Yard, then valued at $250k, as partial payment. That transaction was the final note in his grand agricultural empire play. The great sell-off was over.

It might be tempting to chalk this all up to pressures of the Great Depression, but his spiral and the majority of his sell-out cycle preceded Black Tuesday by more than a year. In fact, following his usual pattern, he emerged from this period in late 1929 flush with cash. And as part of his usual pattern he ramped up his big spending again. This time it was airplanes. He bought his first airplane in October of 1929 mere days before the stock market crash, then the following June he bought one for his daughter Martha and one for his son John. He also started buying big, expensive magic tricks in earnest. The crash itself didn’t slow him down, and the great spiraling sell-off appears to be unrelated.

The decade between 1923-1933 is when his current reputation for being eccentric, alcoholic, moody, etc. took root. You see some smart business decisions and his skill in closing big deals with influential players in key industries. His ability to network and win over business partners with the power of his personality is evident in each of these moves. But starting with the Candler Floating School idea in 1923 (more on that in a future site update) you start to see some fuzzy logic and a return of his inability to balance the cost of his vision with the income potential of the final product, similar to the Atlanta Speedway. You see problems in his personal life causing financial pressures as he’s trying to maneuver business ideas around.

Thanks to the control he had over his father’s Candler Investment Company and the influx of cash from the sale of Coca Cola in 1919, Buddie was able to accrue a diverse enough portfolio of real estate holdings that he could afford to wager on big ideas and more than occasionally lose the bet. A burn-rebirth cycle necessitates some financial privilege, so failure ends in a soft landing, not a crash. Buddie had a cushion, so if he fell he wasn’t a goner.

In 1935-1940 you see another rising phase when he purchased the Robert Fulton Hotel outright, along with a slew of apartment buildings. He also built the Thunderbolt Yacht Basin in Savannah, GA and Briarcliff Laundry.

In 1946 another great sell-off would kick off as costs at West View Cemetery and mounting legal problems drove him into another burn cycle. During the 1946 sell-off he let go of properties including his father’s mansion on Ponce de Leon and the yacht basin. He also started preparations to sell his home, Briarcliff Mansion.

Post script

Candler Warehouse sold again in 1946 when Buddie was selling off other properties. It had been used temporarily as a military ordinance depot, but as the military’s needs ramped down the time was ripe to sell it off. It was purchased for $1.6mm by a Chicago-based cotton brokerage firm. These days the Candler Warehouse still stands and has a new life as The Met, a hub of an arts and design community.

Real Estate Gallery & Resources

The Atlanta Constitution, MArch 30, 1919

The Atlanta Constitution, June 19. 1919

The Atlanta Constitution, January 27, 1922

1930s postcard for The Briarcliff hotel and Apartments. Prior to 1938 the hotel was known as “The 750,”

The Star Tribune, November 11, 1923

The Atlanta Constitution, July 31, 1924

The Tampa Bay Times, February 14, 1925

The Atlanta Constitution, November 1, 1925

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 16, 1925

The Atlanta Constitution, February 23, 1927

The Atlanta Constitution, June 15, 1928

The Atlanta Constitution, June 14, 1928

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 22, 1928

The Atlanta Constitution, August 8, 1928

The Atlanta Constitution, March 15, 1929

The Atlanta Constitution, January 30, 1930

The Atlanta Constitution, January 30, 1930

The Atlanta Constitution, January 31, 1930

The Atlanta Constitution, May 4, 1930

The Atlanta Constitution, October 17, 1931

The Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1935

The Atlanta Constitution, June 11, 1939

The Atlanta Constitution, October 3, 1939

The Atlanta Constitution, July 3 , 1946

The Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1946

The Atlanta Constitution, February 15, 1951