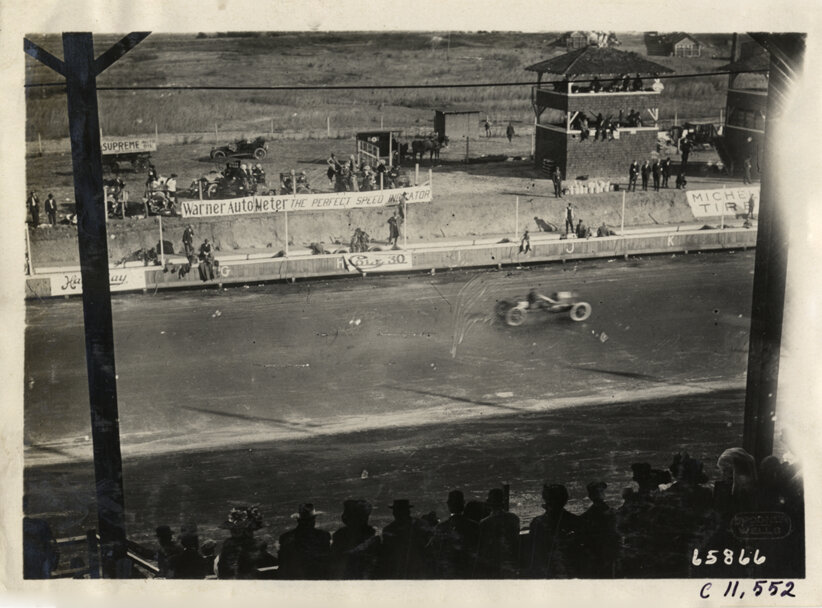

Above: Asa Candler, Jr. (2nd from the right) with racing official pals at the November 1910 Atlanta Speedway races.

Following the November 1909 inaugural races, all public eyes were on the Atlanta Speedway for an encore performance. Internally, the AAA was in turmoil as it grappled with the shortfall in ticket sales, which left the track in deeper in debt than anyone expected after Auto Week. Asa Candler, Sr., was the majority shareholder and stood to gain the most from its success and lose the most if it failed. By the first week of December he had an exit strategy planned and drew up a contract that would extract him from the quagmire of the Speedway’s finances.

December 1909

In a contract on file at the Emory Rare Papers Archive we can get a glimpse into the way Asa Sr. maneuvered his way out of financial risk in case the Atlanta Speedway was unable to meet its projected potential, and how he placed the success or failure of the endeavor entirely in his second son’s hands.

I transcribed the document and translated the antiquated legalese into into plain language as best I could, seen below.

page 1

page 2

page 3

page 4

This agreement is created on Dec 2, 1909, between Asa Candler Jr. and the Atlanta Automobile Association (AAA).

On August 2, 1909, Asa Jr. sold to the AAA the Hapeville land and gave the AAA the bond for title of the property and was partially paid. AAA owes Asa Jr an outstanding balance of $57,000.

Once the AAA took possession of the property it built the track, grandstand, clubhouse, and more, and now owes a total of $73,000 to the construction companies for their work. This is in addition to the $57,000 noted above.

The AAA asked Asa Jr. to pay off its debt to the construction companies, which would mean their total debt to him would be a total of $130,000. The AAA pledged to give Asa Jr. the title to the property and a lien on future gate receipts until they can fully pay him back.

This agreement, which is intended to settle the terms of the deal, states that the AAA is now giving Asa Jr the bond for title for the Speedway property. Asa Jr. will pay AAA $57,000 for this repurchase of the land. Asa Jr. will lend the AAA an additional $73,000 so they can pay the construction companies and settle their debts. The AAA will then give Asa Jr. a promissory note for $130,000 ($73k + $57k) which will earn 7% interest and will be due on or before December 1, 1910. When the AAA finishes paying back the $130,000, Asa Jr will give the AAA a new bond for title and give the AAA the property.

The purpose of the agreement is for Asa Jr. to provide money to finish paying for all of the AAA’s debt and to give him a lien for the AAA's repayment. Therefore, in addition to Asa Jr. paying off the AAA's debts, the AAA agrees that Asa Jr. will have a lien against all ticket revenue for all future events held on the property.

The AAA will collect and hold all ticket revenue as collateral security to be paid against the promissory note owed to Asa Jr., and will continue to do so until all money owed to Asa Jr. is paid in cash. The AAA will first pay operating costs of events and then apply the remainder to what's owed to Asa Jr. The AAA agrees not to use any ticket sales revenue for any purpose other than paying for event operation costs or repayment of debt.

Both parties have shaken hands and signed in agreement.

Signed by Asa Candler, Sr. and Asa Candler, Jr. Witnessed by Edward Clapp

Why would Asa Sr. have structured the agreement this way? Was this intended to shield him from a financial failure that he could see on the horizon once the huge November event fell short of its goal? Was this intended to motivate Asa Jr. to do everything he could to make the business a success, since his personal wealth was now on the line? Was this the action of a father who had been burned before by his son’s poor business management in Los Angeles and Hartwell? We can only speculate, but the maneuvering that minimized Asa Sr.’s risk and maximized Asa Jr.’s risk is evident in this contract.

By the time the contract was in place and the AAA agreed to eject Ed Durant and Ed Clapp, Atlanta was well into the winter months. No one wanted to sit out in the grandstands or race around the oval in frigid temperatures. So at first the association’s upheaval didn’t coincide with any race scheduling and thus didn’t impact their revenue projections.

February 1910

In February, Asa Jr. and Ed Durant fought like two cats in a bag, culminating in Buddie locking Ed out of his office and evicting him from the Candler Building. Given that February is often the coldest month in Georgia, sometimes dipping below freezing, it becomes clear how Buddie intended to make life hard on his ex-friend by shutting off the heat in his office.

Meanwhile, he needed to backfill the two Eds. Fortunately, he was a charismatic, engaging fellow, which made him good at finding allies. His brother-in-law Bill Owens stepped in right away as AAA Secretary. And then Asa Jr. hired a man named James M. Nye, nicknamed “Bill” Nye.

Although as far as I am aware he was not a science guy.

I’ll call him Jim for the sake of clarity. Jim Nye was originally an assistant superintendent of the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, who left prison work to pursue a career as a Secret Service agent in Washington D.C. In 1909 he was stationed out in San Francisco, appointed to an anti-counterfeiting task force and very highly regarded in his field. According to a press statement appearing in the Los Angeles Herald, he left 17 years of government work to accept a long-term contract at the Atlanta Speedway that promised a higher salary than that of his current Chief.

The press statement pointed out the obvious, that managing a racetrack is a far cry from civil service and law enforcement. By all accounts he had no qualifications other than an affable personality and an appreciation for automobiles. But in reviewing Buddie’s full history, it’s no stretch to assume he was enchanted by Nye’s provenance, and that’s all it took for him to hand over the keys to the expensive operation. Starry-eyed as ever over people in romanticized lines of work, Buddie offered Nye the position of General Manager, a generous paycheck, and—according to some accounts—a nice house to live in. When reviewing the timing, it becomes clear that Clapp’s resignation, whether self-motivated or imposed upon him, coincided with Nye’s appointment. Buddie didn’t wait for the ink to dry on the want ad before replacing Clapp with someone new.

As soon as Nye arrived in Atlanta, Asa Jr. went to work putting his name into circulation in an attempt to make Clapp and Durant disappear from memory. Right away Buddie and Nye hopped a train bound for Mardi Gras to discuss a possible race with George Robinson, Frank DePalma and Bill Pickens. Pickens, in his typical pot-stirring way, told the press that if Durant and Clapp were still at the helm of the Atlanta Speedway he and Barney Oldfield would never consider an offer. But now that Asa Jr. and Jim Nye were personally arranging match-ups, he could see doing business with them again. High praise from a controversial figure.

Throughout February, Ed Durant dominated headlines, pushing the narrative that Asa Jr. was a “spoiled child” who treated the track like a plaything. As this drama came to a close, Buddie and Jim Nye ramped up their race planning activities like the conflict had never happened. First things first, they had to get the Speedway bringing in income, so they headed up to New York to recruit drivers for a Spring event. Asa Jr. also batted around the idea of including motorcycle races and putting on an aeroplane exhibition to show off the latest in daredevilry and technology. He needed to come up with a gimmick that would bring out attendees in sufficient numbers to offset the track’s mounting debt. Press coverage from the time makes it clear that it was no secret that the Speedway was hemorrhaging money.

April 1910

Which might be why in April he made headlines again as one of several people who were called to testify to a grand jury in an investigation into illegal “wirehouse” stock trading. He may have been relying on bucket shop gambling to bring in extra income, since the track was so far in the red and he’d tied up his personal money in his Inman Park house and his collection of expensive cars. He’d previously participated in shady tontine insurance to make money, so this wouldn’t have been a stretch for him.

April 2, 1910, The Atlanta Georgian

May 1910

In May the Atlanta Speedway held its spring races. Although Buddie and Jim Nye were able to secure some big-name drivers like Ray Harroun, they were unable to bring in enough celebrity drivers to fill out the event. Instead, they padded the line-up with local amateur drivers. Asa Jr. raced his own Fiat against his pals, like Bill Stoddard, father of modern dry cleaning, who appears to have been one of his best friends during the aughts, teens, and early 20s. Due to low interest, they failed to turn out a significant enough crowd to turn a profit, and the lackluster newspaper reporting reflects a ho-hum response to the event.

May 6, 1910, The Atlanta Georgian

In the meantime Buddie was busy righting his upended public image by securing a full-page puff piece about himself in a weekly publication called The Greater Atlantan. The full transcript of the article is provided at the bottom of this page. Based on the aggrandized claims of his success, as well as the grammar errors consistent with his personal correspondences on file at the Emory Rare Papers Archive, I believe he wrote the article himself in the hopes of convincing the public that he was not the man the press had made him out to be. Here’s just a sample:

“Greater Atlanta and her progressive movement among the greater cities of the country could not be better emphasized than in the life of Asa G. Candler, Jr.

Wide awake at all times, progressive in everything he undertakes, with an intuition to seize upon things for their true value and a knowledge of business affairs and financial business that is remarkable, Mr. Candler ranks with the best of the business men of Atlanta today.”

He also made several boastful statements to the papers in response to the rumors that the AAA and Atlanta Speedway were struggling to stay afloat. He claimed that the Speedway was a runaway success, and told the Atlanta Journal that he was presently planning to build a $100k “palace” in Druid Hills, a monstrous price tag for 1910 and clearly an effort to show how much money he was making on the endeavor. Then he flipped and claimed that he was so busy with successful business opportunities that he may move to New York permanently and leave Atlanta behind, abandoning the track and the hypothetical mansion plan.

As he spun yarns and dodged rumors throughout May, he was also busy liquidating assets, which only fueled speculation that he was struggling to stay afloat. He sold his seat on the New York Cotton Exchange that he’d only acquired in January, and he reportedly sold one of his prized racing Fiats. Liquidating assets, stalling his plans to break ground on a house, participating in risky wirehouse gambling, it all suggests that he was juggling his finances during a time when he needed to appear successful to the public eye.

Then suddenly the churn came to a halt as he made an important announcement: He had purchased a Lozier.

The Daily Times Enterprise, May 17, 1910

Lozier was a luxury automobile brand of the highest order. Intricately engineered and finely finished, Loziers were some of the most expensive cars of their time, listed at more than five times the price of a luxury Cadillac. This purchase cost Asa Jr. more than $5000 ($122k in 2019 money) and was the ultimate status symbol, He needed one of those badly so he could thumb his nose at his detractors. Based on timing and activity before and after the purchase, it’s likely the aforementioned financial juggling was done especially for this acquisition, adding to his already notable collection of 5 other premium automobiles.

Allow me to be specific, because I was able to put together enough clues to pinpoint the exact make and model: Asa Candler Jr.’s Lozier was a 1910 4-cylinder, 45hp Briarcliff H-model with rear tonneau.

Yes, Briarcliff. Atlanta residents, take note.

The short version of the generally accepted history is that the Lozier company developed this model especially for the famous Briarcliff road race, which ran in Briarcliff Manor, NY, as a companion to the Vanderbilt Cup. Lozier named their new model the Briarcliff in honor of the race. It was designed for peak performance over long distances on real-world roads in both endurance and speed. And it was beautiful, too.

1910 Model H Lozier Briarcliff, likely very similar to the one owned by Asa Candler, Jr.. Source: Conceptcarz.com

June 1910

It was a superlative car for a man who lived for superlatives. And it was designed to do exactly what he planned to do with it: drive it from Atlanta to New York in a road race called the Good Roads Tour. In 1909 the Good Roads Tour ran from NYC to Atlanta and ended with the participants taking a victory lap around the new speedway. In 1910 they reversed direction, and the line-up of drivers was a who’s who of the Atlanta amateur driving scene, including Ed Inman and Henry Heinz.

Notable in the list of entrants was Edward Durant, who chose to make the trip with his wife and children in his personal Pope Toledo, which was registered in the same class as Asa Jr.’s Briarcliff.

Edward Durant on the road with his family, ATL to NYC Good Roads Tour, 1910.

The objective of the tour was to demonstrate endurance and speed by making the trip in the shortest amount of time with the fewest mechanical faults. Timers checked speed and odometers and kept a running score for each entrant. They stopped together in various cities along the route, and the huge line of cars caused a stir everywhere they went. Some cars dropped out along the way, simply unable to handle the mechanical stresses of the trek. Most arrived successfully in NYC and were greeted by Mayor Gaynor at the New York Herald building. 62 cars started, 48 finished, and only 7 arrived with a perfect score. Of the 7, 3 are familiar names by now: Ed Inman in a Pope-Hartford, Ed Durant in a Pope-Toledo, and Asa Candler Jr. in his brand new Lozier Briarcliff.

The Lozier company was thrilled with the result and asked him right away to participate in a nationwide campaign to publicize his success. Diamond Tires wanted to advertise his achievement, too. Suddenly, after so many bad headlines, Asa Jr. was getting high praise and free press, all thanks to his Briarcliff.

Pay attention to the opening paragraph of each Lozier ad. Reputable auto racing reporters covering the event noted seven finishers with perfect scores. Ed Durant’s car was in the same class as Asa Jr.’s Lozier. But the Lozier ad says it was the “only car with a perfect score in the Big Car Class in which it competed (except one car which may be given a Perfect Score although admittedly late at one control).” The jab at Durant’s shared accomplishment was no accident. Pure shade.

The Baltimore Sun, June 16, 1910

The Star Tribune, June 26, 1910

The New York Times, June 17, 1910

The Atlanta Constitution, June 19, 1910

Of course, it should be noted here that he didn’t drive his own car, at least not for most of the drive. He had a driver named Frank Hardaman McGill Jr., also known as Mack. Mack McGill was a registered chauffeur in the Atlanta Area before becoming Asa Jr.’s personal driver. He sometimes raced his boss’ cars at the track, and he did most of the driving on road tours. By 1914 he decided to move on to new endeavors and opened the Miami Cycle Company in Miami, FL, but in 1910 he drove most of the route from Atlanta to New York in 1910, while Buddie took the headlines and credit as the skilled driver whose amazing automobile had made the journey with a flawless performance.

This was Asa Candler, Jr.’s finest hour, his defining moment, his brush with b-list celebrity status. From coast to coast, in virtually every market, the automobile column in local newspapers across the country mentioned the results of the Good Roads tour. Buddie was a minor star. Briefly.

Riding the high of the favorable press coverage, Asa Jr. promoted Jim Nye, and together they dove straight into planning the summer races, which were scheduled to take place at the end of July. But once again he had trouble booking the big names in pro racing. Like the spring races, he filled out the roster with local amateurs, including Mack McGill, Jim Nye, Ed Inman and Bill Stoddard, as well as his brother William and their brother-in-law Bill Owens. The race line-up looks like an event purely for Asa Candler, Jr'.s inner circle of associates.

July 1910

He entered his Renault and the infamous Fiat-60 that he’d purchased off of George Robertson in the 1909 debut races. William Candler’s SPO was noted as “the most dangerous car in its class.” Ed Inman entered a Simplex and Bill Stoddard entered a National that he raced frequently. All of them designated drivers to race on their behalf, with Mack McGill listed to drive Buddie’s cars.

In a fun exhibition, Buddie and Jim Nye staged a 1:1 race where Buddie proved he could circle the track twice in his big Fiat in the time that Nye took to make one lap in his little Fiat. Buddie wagered 33 cents against Nye’s 66 cents and took a 15 second handicap. The big Fiat won, beating the baby Fiat by only a second or two.

For the rest of the event, the line-up was lean. While many events were listed, the same names repeated throughout the roster, making each race very similar to the one before. Predictably, the ticket sales weren’t great. Worse, the skies opened up on Saturday, July 23, and rained the event out. Rain checks were issued, the roster juggled around a bit, and they spent the following week patching up the track and preparing for the following Saturday. To encourage folks to come out, Asa Jr. had a pal over at the Atlanta Constitution write a puff piece on his behalf to get potential customers excited.

“Howard Spohn, special representative of The Automobile and Motor Age, a noted automobile expert, visited the track yesterday afternoon as a guest of Asa G. Candler. After looking at the track he said, ‘There is no hope of making me believe that this is as smooth as Indianapolis.’

’You’ll eat those words,’ replied Secretary Nye. Shortly afterwards Mr. Spohn was taken around the track in Asa Candler, Jr.’s prize-winning Lozier, winner in the New York to Atlanta run. The machine hit a 50-mile an hour clip and slipped around the course as smoothly as though running on glass.

’I take it back,’ was Mr. Spohn’s comment before the circuit was finished. ‘It rides about ten times smoother than it looks and it is certainly better than Indianapolis.’

That means, of course, that it is better than anything in all America.”

Notice how the story has now evolved to declare Asa Jr. the “winner” of the Good Roads tour.

The July race ticket sales didn’t dig the AAA out of debt. And by now the rumors were swirling about the upcoming December deadline when the mortgage, held by Asa, Sr., would come due. There weren’t enough puff pieces in the world to make Atlantans forget the tenuous path their relatively new speedway was on.

August 1910

In August Buddie sued a child for striking a match on his car. This has nothing to do with the Speedway, I just like the absurd pettiness of the story.

The Atlanta Georgian, August 27, 1910

By now planning for a smaller September race was underway, as well as planning for the November races, marking the 1 year anniversary of the track’s opening. It needed to be a big event, and this was their last chance to bring in enough money to pay off their construction and vendor debt, as well as pay down the looming mortgage. The clock was ticking.

September 1910

Unfortunately, Jim Nye was unable to recruit enough drivers for the September event and the races were called off. To distract from the embarrassing press, Buddie announced that he would embark on another tour in his winning Lozier. He called it the “‘round the state tour,” and traveled the state of Georgia in his open-top Briarcliff with friends Frank Weldon, J.S. Cleghorn, and Frank Fleming along for the ride. And of course Mack McGill shared the load as driver and mechanician.

The Atlanta Constitution, Sept 25, 1910

Buddie hit the press hard. On the same date three articles were published in the Atlanta Constitution that hyped his and the track’s rep. One article announced that Asa Jr. would let a well-liked stage actress, Florence Webber, drive his big, famous Fiat. Another disclosed plans for a spectacular matchup between baseball legends Ty Cobb and Nap Rucker. The third overflowed with admiration for Buddie’s ‘round the state tour.

The total mileage of just the segment from Atlanta to Augusta was 177.1 miles, and took seven and a half hours, including stops for meals and entertainment. The average speed was 23 miles per hour. The following is an excerpt from one of the two multi-page articles that appeared in the Constitution that day

“Asa G. Candler, Jr., upon his return yesterday, said that the route of the All-Round-the-State tour is fine.

Although he had been through a week’s strenuous work, he looked hard as iron, and said that he now felt better. He and all the party were bronzed until their faces and hands matched in color their khaki suits. He loves to drive, and is not averse to some speed, but he is careful and skillful.

Twice he was driving until far into the night, but he was always ready to be up and off by sunrise or before. He is thoroughly game, and was just as anxious to make the circuit in six days as I was.

That he was driving far into the night on two runs was no fault of his or of his car. He was in the seat at the wheel for twenty-two hours on one run, except for the time taken by entertainment and helping another motorist who was in trouble.”

Then the Wilmington Morning Star picked up an article about what makes the best drivers so good, and included Asa Jr., in their list of men with the physical prowess to win a race, along with the big names like Robertson, Mattson, Strang, and Oldfield. What made great drivers great? Brute power, said the writer. He declared that all great drivers were “beefy” men.

What followed was a thinly veiled advertisement for the Atlanta Speedway. It recapped the heroism of the manliest of manly drivers, noted Asa Candler, Jr.’s fine physical qualities, and promoted the upcoming November races.

“...All these are big men and strong. And their very strength has been a tremendous advantage to them in the racing game. ...When it comes to rounding turns and dodging in and out among racing cars it takes wonderful muscle and weight as well.

There was an example this summer on the Atlanta Speedway. In the early practice for a local meet F. H. McGill and Asa Candler, Jr., did all the tuning up for Mr. Candler’s giant Fiat-60. This is a car which is particularly vicious at steering. It yanks and bucks and raises sand, especiallly on the turns. In every practice spin Mr. Candler could get two or three seconds better time for a round than his driver. Both men are equally fearless and equally skillful. The secret lay in weight and proportionally more strength.”

One thing I found notable in this article is that the writer refers to all of the other men either by last name, or, in Barney Oldfield’s case, by first name. Only Asa Jr. is mentioned as the formalized “Mr. Candler.” Similar to previous puff pieces I’ve mentioned, I believe Buddie had this article commissioned and sent around for local papers to pick up.

October 1910

Atlanta was abuzz with the preparations for the upcoming races. Cars were loaded up and shipped from all over, Ty Cobb and Nap Rucker were lined up for their big matchup, and Lozier sent a “brigade” of cars to participate. 53 cars were registered, the largest roster yet recruited for a single event at the track. Asa Jr. and Jim Nye even arranged for an aeroplane demonstration to take place in the center of the racing oval between events. They had spared no expense to make the event successful, including paying the freight fees to bring in drivers’ cars by rail. Sparing no expense was part of the problem. Buddie never spared any expense, but he also never made sure the cost structure made sense. As the December debt deadline loomed, he spent more than he could possibly offset with ticket sales, even if the event was a smash success.

Much of the press coverage demonstrates once again how the event pivoted around Asa Jr. and his inner circle of racing pals. Bill Stoddard drove Asa Jr.’s Fiat after the rough steering tore up Mack McGill’s hands. Baseball manager for the New Orleans Pelicans, Charlie Frank, came out for a friendly visit, and Buddie took him on a blitz around the track for a laugh. It was all fun and games for the wealthy Atlanta auto racing insiders.

November 1910

On November 3rd the 3-day race event kicked off. The number of entrants dropped from 53 to 46, although that was still a good number. Ty Cobb had to call off the highly anticipated matchup with Nap Rucker or risk a penalty to his baseball career. And Barney Oldfield got himself disqualified from all sanctioned auto races and could no longer participate. This didn’t bode well.

Photos of the event speak for themselves. The grandstands were notably emptier than the previous year. They also failed to draw as many track-side spectators who had filled the center of the oval in and parked along the inner embankments to watch the action up close in 1909.

Sparse Grandstands, November 1910, The Atlanta Speeway

sparse Grandstands, November 1910, Atlanta Speedway

Starting Line-up with sparse grandstands, November 1910, Atlanta Speedway

Sparse Grandstands and Inner Embankment, November 1910, Atlanta Speedway

Even with a demonstration of flying by a daring pilot in a fragile contraption failed to bring out the crowds.

\Flint Flyer airplane, designed by Buick engineer Walter L. Marr and manufactured by the L.A.W. Aeroplane Company in Flint, Michigan. Atlanta Speedway, November 1910 Races. Read more about Walter Marr here.

That’s about how I would feel, too. Atlanta Speedway, November 1910 Races

On November 5th the 1910 November races ended not with a bang but a whimper. To offset the embarrassment of the track’s low attendance, Asa Jr. re-ran his personal puff piece from the Greater Atlantan in the Atlanta Constitution, even though it remarked on the “upcoming” November races three weeks after they had run. His reputation as a businessman was under public scrutiny again and he knew it. But the reality was that they didn’t pay down their debt, vendors were still waiting for their share, and public interest was waning. And the track’s struggle to prove its financial viability was widely known. A December 21st issue of Horseless Age pondered whether Atlanta could rally enough interest to keep the venture going much longer.

Asa Candler, Sr., was running short on patience. A year after he put the financial burden directly on Asa Jr. to make the Speedway project work, he called in the debt and together father and son faced the harsh reality of closure.

January 1911

In January, Asa Jr. ran a last gasp of a PR effort by shopping around a story about his 4-year-old son John, who he claimed was a crack driver. He successfully pitched the tale to several newspapers, and with every publication it evolved and became more outrageous. Clearly it was meant to be taken in good humor, but the story also reeked of the kind of aggrandizement that Buddie was known for.

The Washington Herald Sun, Janjujary 15, 1911

San Francisco Chronicle, Sunday January 22, 1911

Interestingly, I found a set of photos taken at the November 1910 races that likely inspired the cockamamie story. John did indeed sit behind the wheel of his daddy’s famous Lozier, and those photos are certainly charming. But the story that made the rounds in January seems engineered to create a legend.

John Candler behind the wheel of his father’s Lozier Briarcliff, November 1910

John Candler behind the wheel of his father’s Lozier Briarcliff, November 1910. Asa Jr. can be seen out of focus on the left in the background,

John Candler Standing with his father, seen in the shadows with his trademark cigar. November 1910

John Candler drinking a coca cola with his father in the background, November 191o

And that’s it. The Atlanta Speedway was done. Over. Finito. All media coverage of the track halted completely, and the next time the track came up was in retrospect after the land transitioned to its new life as an expanse of open field with an indeterminate future. Jim Nye resigned and returned to California, where he went back to his old job in law enforcement and made headlines in August of 1911 when he helped to bust up a counterfeiting ring.

As for Asa Jr., the failure was a very public hit to his image. As before, he had to demonstrate that he was bigger and more important than this one small failure. But instead of running puff pieces and making blowhard statements to the press, instead of purchasing a winning Fiat race car or laying out big cash for a luxury Lozier, he thew a Hail Mary.

My forthcoming book about the life of Asa Candler, Jr., is titled Asa From the Ashes, drawing a comparison between Buddie’s cycles of successes and failures and the mythical phoenix, which cycled similarly between resurrection and immolation.

In February of 1911, Asa Candler Jr. chose immolation and became the phoenix.

The Fall of the Atlanta Speedway Gallery

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Herb Lytle in an American Speedster, Atlanta Speedway, May 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Thank you to Kelly Williams of Stanley Register Online for identifying Herb Lytle and his American!

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Atlanta Speedway, November 1910

Aeroplane Exhibition, November 1910

The Greater Atlantan, May 1910 Full Text

“Asa G. Candler, Jr.

President Atlanta Automobile Association, Owner of World’s Greatest Speedway

Greater Atlanta and her progressive movement among the greater cities of the country could not be better emphasized than in the life of Asa G. Candler, Jr.

Wide awake at all times, progressive in everything he undertakes, with an intuition to seize upon things for their true value and a knowledge of business affairs and financial business that is remarkable, Mr. Candler ranks with the best of the business men of Atlanta today.

Mr. Candler is of the type that always succeeds. He comes from a family of successful men. His father, Asa G. Candler, is one of the city’s leading financiers, bankers and capitalists, and his son inherits all his good qualities.

Mr. Candler is a native Georgian, born in Atlanta and living in Georgia all of his life, with the exception of two years. He is 30 years of age and married.

The Candler residence on Euclid Avenue is one of the most beautiful of the palatial homes in the city today. Mr. Candler is constructing now a handsome home on the Williams Mill road, which will be ready for occupancy by the 1st of next April, his home on Euclid Avenue having been sold.

The two years of Mr. Candler’s life which were not spent in the Empire State of the South were spent on the Pacific Coast, inaugurating the fine Coca-Cola factory that now stands as a monument to his name even in that far away clime. Mr. Candler spent two years in Los Angeles superintending the construction and operation of this factory and getting the business upon a

firm, substantial business basis.

Mr. Candler lived in Hartwell, GA, for the best part of six years, managing a cotton mill, and it was due to his excellent management that the mill succeeded. Everything that the young financier seemed to touch about this time succeeding (sic) admirably. While living in Hartwell he married the present Mrs. Candler.

Mr. Candler returned to Atlanta in 1907 and has been a resident of this city ever since.

He is the renting agent of the Candler Building, the Candler Annex, and Commerce Hall. The conducting of these ventures, which are enormous in themselves, require (sic) painstaking study and thorough and most careful management, he has shown himself capable of giving (sic). His main duties in this connection are to collect the rents of the offices in three buildings

and to see that everything is kept repaired and in their best condition.

Mr. Candler is the president of the Atlanta Automobile Association. In the organization of this company came the chance for his fine executive ability and financial genius to have full sway and he showed himself capable of handling what has proven at times a weighty problem, though it now bids fair to be one of the many great Candler successes.

In the summer of 1909 the idea struck Mr. Candler that the building of an automobile race track in the city of Atlanta would be the means of a big advertisement to the city of Atlanta at large throughout the entire world.

The building of such a track, which in Mr. Candler’s mind, should be the best in the world, meant a tremendous undertaking, but he was equal to the occasion. He talked the matter over with several of his business associates and called a meeting of over a hundred members of the chamber of commerce. They met in the chamber of commerce room and discussed all the sides of the proposed track from all angles. Mr. Candler had previously taken trips to every big track of note and was well versed on the different points at issue.

He told just how much it would take to build this and that, itemizing each item until he had a total cost figured out. The first move was to choose a suitable tract of ground, which was done. In fact, Mr. Candler had chosen the proposed site before the meeting was even called.

So earnestly and with such an air of knowing just what he was doing did Mr. Candler present the real good to be obtained from a good automobile track, stressing the great advertising that the city of Atlanta would get as the principal feature, that when a subscription list

was started half of the required paid-in capital of the company was subscribed to before the meeting adjourned. Mr. Candler and Mr. Candler, Sr., headed the subscription list and they were followed by several others until the amount had run up into the thousands.

From the jump the track was a go. It proved to be not only the fastest but the safest track in the world. The first meet last fall was a huge success, as was the amateur meet this spring.

But the meet this fall.

This meet is going to far surpass anything ever attempted by any track. Not only has the local association through Mr. Candler offered the greatest prizes ever heard of for a splendid card of events, but the entries that have poured into the local association is (sic) indeed wonderful. Fully seventy cars will be on the track when the first races are run on the opening

day.

The Atlanta Speedway is a tribute to the untiring energy of a young business man, firm in his convictions that he had a winning proposition, and in years to come will be recognized world-wide even on a more greater scale than it is now.

Young men like Mr. Candler, Jr., are a credit to any community.”