Above: Asa Candler V (L) and Landrum Anderson (R) Source: “The Real Ones” by Elizabeth Candler Graham

What you see here is the only known photo of Landrum Anderson, lifelong employee of Asa Candler, Jr. I want to share a bit about him, because history often overlooks the way wealthy White Southerner’s lifestyles of excess and leisure were made possible by Black servants in the decades after slavery ended.

Asa v (L) and Landrum Anderson (R)

Originally shared 1/2/2018 on shbutlerwrites.wordpress.com

Who Was Landrum Anderson?

Landrum, known as “Brother Landrum” according to Candler family lore, was the lifelong servant of Asa Candler Jr., owner of Atlanta’s Briarcliff Mansion. Landrum and Asa Jr. met in 1901 in Hartwell, GA, during the brief period when Asa Jr. ran his father’s North Georgian cotton mill. When Buddie returned to Atlanta in 1906, Brother Landrum came with him. Family lore says it was Buddie’s wife Helen who insisted upon retaining Landrum and allowing him to move to the city with them.

When Asa Jr. and family moved from N. Jackson St. to Inman Park, Landrum moved with them. When they relocated to Briarcliff Farm, Landrum went with them. When they tore down the farmhouse and built Briarcliff Mansion, Landrum was there. He lived in a small house on the back property, rented at a price of $1 per month from his employer. That’s about $15 per month today. And, according to family lore, Brother Landrum was there until the end, still working for the family when Asa died in 1953. In Buddie’s will, he left $8500 to each of seven servants (more than $80k in 2020 dollars), one of whom was undoubtedly Landrum. He lived only one more year after his boss’s death and passed in 1954. He spent over 50 years of his life serving the Candler family

Landrum is unusually persistent through Buddie’s history. A common element I’ve found in my research into the life of Asa Candler Jr. was that he had few relationships that lasted for very long. He had some friends and servants who stayed with him for years, but no one other than blood relatives stuck by his side like Landrum Anderson.

But who was Landrum Anderson? That’s not an easy question to answer.

The Southern Problem

Brother Landrum was born in the rural South in the post-Civil War era. This was a murky time for records of Black Americans. During the slavery era, slaves were often listed as property belonging to the slave owner, not as people with vital records. The 1870 census was the first record that captured African Americans by name, but it’s hardly complete. Even if names were captured, they could have been changed upon emancipation and birth names lost to history. Residences often changed with few records to follow. Jim Crow laws suppressed voter registration, so those records are spotty for decades. We have very little to go on if we want to trace his history and find his family. All we have Is a name in four census records and family accounts given by Asa Jr.’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren. You’d think that might be enough. It’s not.

Hard Data

In 1910, Landrum Anderson first appears on a census at Asa Jr.’s house in Inman Park. He’s listed as 40 years old, and his occupation is listed as butler. Elsewhere in the record it’s noted that he cannot read or write. He was the only servant on staff at the time. Also listed as a resident is Helen’s brother William, who was granted employment by his brother-in-law as a machinist at the Candler Building. Asa Jr. had a long history of finding jobs for people in his inner circle, or using jobs to pull people into his inner circle. But that’s a story for another day.

1910 Census Record

In 1920, Landrum appears again as a servant, this time living at Briarcliff Farm with the Candler family. Other servants who stayed with the family are also listed. Landrum’s wife Jessy (maid) appears, as do Fanny Upshaw (cook) and Eli Johnson (chauffeur – automobile).

Once again Landrum is noted as 40 years old. If I’ve learned anything from old census records it’s that no one really cared much about capturing the correct vital stats of servants, especially if they weren’t White. Sometimes they didn’t even bother spelling their names right. In the 1920 record all staff are noted as literate, although it would not be unusual for this to be inaccurately reported.

1920 Census Record

Now we get to the 1930 census record, seen below. On this one the census taker noted in the margin “West of Briarcliff Rd (Candler Estate)” across several names. Most of the names are listed in labor type jobs and the locations are listed as “private estate.” Through other research I can confirm the Cruz brothers as butler and valet and James Stark as the groundskeeper. My assumption is that all names between the Candlers and Mary Anderson were Briarcliff staff members and their families. This shows how the staff size ballooned once Briarcliff Mansion took shape.

In the 1930 record Landrum is listed as 25 years old. His wife’s name is spelled Jessie instead of Jessy, and their daughter Mary appears, noted as 6 years old. This time it says Landrum cannot read or write. By contrast, it says Jessie did not attend school but can read and write.

1930 Census Record

Then we come to the 1940 census record, the last one available since the 1950 census won’t be made public until 2022. In this one Landrum’s information is different. It’s individualized, less generic. His birthplace is listed as South Carolina. His age is 67 instead of an incremental number ending in 0 or 5. And this time his name is spelled Landers.

1940 Census Record

Jessie’s name is spelled consistently with 1930, but Mary is now Alice, and she’s listed as Adopted Daughter, age 16. Her age makes sense if she was 6 in the previous census, but why did her name and relationship change? Was Landrum her father or not? More importantly, is Landrum’s legal name actually Landers? What the heck happened in 1930? Did someone who didn’t care to know much about the servants rattle off names and fudge the details? Possibly.

And then there’s the death record.

Landrum Anderson’s Death record

But here, too, we have problems. If he was 67 at the time of his death, why was he listed as 67 in the 1940 census record? Which age was correct? Which of any of the ages was correct? If the 1910 record was correct, he would have been born in 1870, and would have been 84 at the time of his death. If the 1920 record was correct, he would have been born in 1880 and would have been 74 at the time of his death. If the 1930 record was correct he would have been born in 1905, 4 years after he met Asa Candler Jr. I think we can comfortably discard the information in the 1930 record. If the 1940 census was correct he would have been born in 1873 and died at the age of 81.

My concern here is that the information in his death record, his age and spelling of his name, was copied over from the last census. It’s as questionable as any of the other records.

So when I go searching to find out where Landrum came from and whether he had any other family, what do I do? Do I search for Landrum or Landers? Do I search for a birth date of 1870, 1873, 1880 or 1887? What if none of those are correct? Do I search for a birth location of Georgia or South Carolina?

Side Note About Location

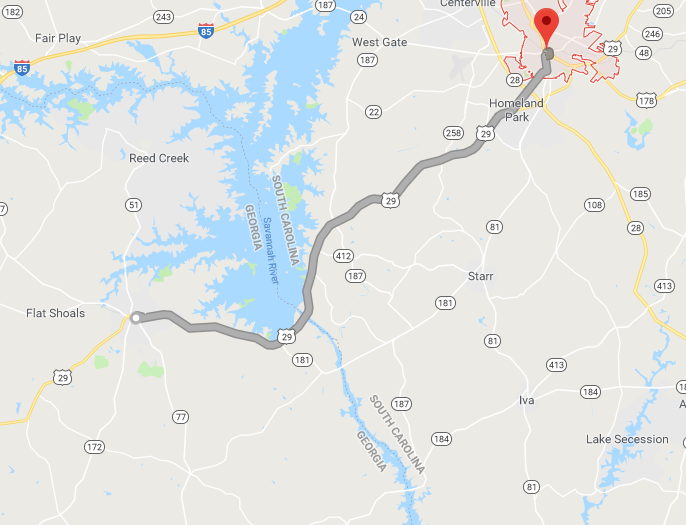

I hadn’t questioned where Landrum was from until very recently. I just took it for granted that he met Asa Jr. in Hartwell, GA, and most of the documentation I could find said he was born and raised in Georgia. Then I found the 1940 census where his name was different and the information seemed more specific. His birth place in that record is South Carolina. Was I wasting my time looking for family in Georgia?

I did a Google search, not really optimistic but sometimes Google gets its little fingers into unexpected sources. I got some hits for the phrase “Landrum Anderson,” like social media profiles for living people of the same name. Then I saw one where the person’s last name was “Landrum” and they were listed as living in a town called “Anderson.” I clicked just out of curiosity. Anderson… South Carolina… Wait a minute…

Hartwell, GA to Anderson, SC. Just 23 miles.

I had made the assumption that Anderson was a surname adopted from his family’s former slaveholders. That’s still plausible, but I realize now that it could have come from the town in which his family lived. If you look for the surname Anderson in Anderson, SC, during the immediate post-Civil War era, you’ll find a large number of African American results. And the city of Anderson wasn’t named for a slaveholder. It was named for a Revolutionary War hero. The people in these records were probably named after the location, not a family.

Then I looked at Anderson’s history. It was a cotton town, a mill town, the first fully electrified town in the South with an electrically powered cotton gin at the mill. In 1901, a flood knocked out the hydroelectric dam that supplied power to the mill, putting it out of commission. The town remained dark until 1902. So in 1901 a lot of mill workers were put out of work. In 1901 Landrum Anderson met Asa Jr. at Witham Cotton Mill in Hartwell, GA, the next closest mill town, just 20 miles down the road.

It’s all speculation, of course. I still can’t find anything to confirm Landrum’s existence prior to the 1910 census. I have nothing for 1900 and the 1890 census was mostly destroyed in a fire. That damn fire made researching Candler residences in Oxford, GA quite a challenge, too.

In another interesting research side-journey, I found that South Carolina has another location-based coincidence for me to ponder. In northern SC, about 60 miles from Anderson, there’s a section of the state comprised of three towns at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains. This section is known historically as the “Dark Corner.” The Dark Corner was the only part of South Carolina that stood with the Union and refused to vote in favor of a measure to reject federal law on the cusp of the Civil War. Their refusal to be “enlightened” in the eyes of those who wished to fight for state’s rights (code for slavery), landed them with this nickname. One of the three Dark Corner towns was Landrum, South Carolina.

The Dark Corner of South Carolina: Glassy Mountain, Gowensville, and Landrum.

Could be a coincidence. Hell, the location of Anderson could be a coincidence. Or it could be confirmation that Landrum’s names were drawn from locations, which would not be terribly unusual at the time. Perhaps Landrum was indeed named Landrum rather than Landers and he was indeed born in South Carolina. At this point I can’t discard or confirm any hunch or lead.

Two More Dead Ends

In trying to identify Landrum’s family I did discover one tentative lead to explore: a brother, or at least someone I suspect was his brother. Lucy Candler, Asa Jr.’s sister, employed a man named Henry Anderson, and he appeared on the 1930 census under the household of Lucy’s second husband, Henry Heinz.

1930 Census Record for Henry Anderson

Henry is listed with a nice round number, age 50. Black, widowed, illiterate, and of course born and raised in Georgia. Probably no more accurate than any of Landrum’s information, although I do find the detail that he was widowed to be oddly specific. Regardless, simply because of the shared names and the close relationship between their employers, I am considering a possible link between Henry and Landrum. Unfortunately Lucy’s life was a tumultuous one, and her household situation changed frequently enough that her census data shows all different locations, cohabitants and staff on each record. Henry only shows up this one time. I can’t find a shred of information on him otherwise.

My final lead came from one of Asa Candler Jr.’s great grandchildren, who I reached out to directly for family information. He knew of a woman named Lula Mae Ware, and according to his memory she was one of Landrum’s relatives. She worked for Buddie’s second daughter, Laura, and passed away in 2012 just before her 101st birthday.

“Mother Lula Mae Winston Ware was born on December 18, 1911 in Opelika, Alabama to Lizzie Lee Winston and Louis Robinson. In 1932 she moved to Atlanta and began her career working for Mr. Edgar Chambers, Jr. and wife, Laura Candler Chambers, daughter of Asa Candler, Jr.”

I found her name in the 1920 census with her family in Alabama. I’ve dug into each of her immediate family’s names, as well as other names listed in her obituary. But despite of Asa Jr.’s descendant’s memory, I can find no connection to Landrum. So once again I’ve hit a dead end.

How Historians Perpetuate Racism

As mentioned at the start, most of what we know about Landrum comes from the anecdotes shared in “The Real Ones,” by Elizabeth Candler Graham, who interviewed elderly children and grandchildren of Asa Jr. While I commend the author’s choice to capture the servants’ histories, the book paints a rosy picture of the Candlers’ relationships with their employees, and depicts the inequity of the power structure as charming and even generous. And it never questions or goes deeper to research the anecdotes, simply recording them as undisputed history. The book contributes to the chronic problem of White-controlled historical narratives skewing our view of the past.

For example, the book includes a story about how Buddie and Landrum met in Hartwell, GA. According to family lore, Buddie met Landrum as a prison convict laborer who worked on mill repairs and agreed to spy on the other convicts and report back to Asa Jr.. Supposedly he’d murdered a man who messed with his wife, and Buddie went to the governor to win Landrum a pardon. That’s why he was loyal to Buddie for the rest of his life. Or so the story goes.

But that story is likely fabricated. No records exist to substantiate that Landrum was ever in prison for murder or any other offense. Absolutely nothing exists to validate the story. It came straight from Buddie’s mouth as a humorous but likely fictitious tale. His penchant for inventing big, zany stories is well documented, and the others on record are equally dubious when compared to historical evidence. Each has a teeny kernel of truth that can be verified, with a tall tale built around it. Landrum’s criminal history is less likely to be true than his more probable past as a migrant mill worker.

The book also contains a story about Landrum being a philanderer, and how his employers forced him to choose between two girlfriends and marry the one he preferred. Another story discusses his moonshine still, and how Buddie permitted him to be taken to jail for illegally distilling alcohol on his property. Yet another tells of a fit of murderous rage when Landrum nearly attacked a white chauffeur with a knife when the man sassed Helen Candler. And of course, there are plenty of references to his unwavering love for Mrs. Candler, shared in the most condescending terms.

What do his stories depict? A hopelessly besotted servant who coveted his employer’s wife, a redeemed murderer, a philanderer, and a boozer. Four sins all rolled together and preserved as one man’s legacy. Unfortunately, these are not uncommon depictions of Black Americans when White memories of that era are consulted.

In the same book, anecdotes claim that the servants were treated well and were respected, while depicting them in quite racist terms, using pidgin English to put words in their mouths, and condescendingly describing their actions as though they were naive children. The author included a disclaimer to excuse the overt racism as a generational holdover, but is that a sufficient excuse to capture racism and move it forward into the historical record?

White historians have to do better. We cannot hand-wave language choices that perpetuate harmful racial stereotypes. Preserving history does not obligate one to reinforce harmful ideas. In a future entry I’ll share my thoughts about whether the Candler family was racist, both by our current standards and within the context of their era. It’s a complex subject without a simple answer. But these are complex topics that deserve to be examined, unpacked, and discussed in good faith. If we are to be good stewards of history, we must be willing to put in the work.

In the meantime, if you have any thoughts about how to further my research and discover more about the real Landrum Anderson, please send me an email through my Contact page.